"Golden Books" - Exploring the Universe

|

Exploring the Universe

|

|

|

![]()

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory

Batavia, Illinois

Operated by Universities Research Association, Inc.

Under Contract with the United States Department of Energy

Introduction

Edward W. ("Rocky") Kolb, head of the Theoretical Astrophysics Group at Fermilab, loves to explore the Universe. Starting from initial conditions in his hometown of New Orleans, he received a Ph.D. in particle physics from the University of Texas at Austin, and worked as a postdoctoral fellow in the Kellogg Radiation Laboratory at Caltech under Willy Fowler. Kolb continued to pursue astrophysical frontiers in the early 1980s as the J. Robert Oppenheimer Research Fellow in Los Alamos. In 1983 he came to Fermilab to explore the inner space/outer space connection by starting the first NASA/ DOE astrophysics collaboration at a national laboratory. He is also a professor of astronomy and astrophysics in the Enrico Fermi Institute of The University of Chicago.

Edward W. ("Rocky") Kolb, head of the Theoretical Astrophysics Group at Fermilab, loves to explore the Universe. Starting from initial conditions in his hometown of New Orleans, he received a Ph.D. in particle physics from the University of Texas at Austin, and worked as a postdoctoral fellow in the Kellogg Radiation Laboratory at Caltech under Willy Fowler. Kolb continued to pursue astrophysical frontiers in the early 1980s as the J. Robert Oppenheimer Research Fellow in Los Alamos. In 1983 he came to Fermilab to explore the inner space/outer space connection by starting the first NASA/ DOE astrophysics collaboration at a national laboratory. He is also a professor of astronomy and astrophysics in the Enrico Fermi Institute of The University of Chicago.

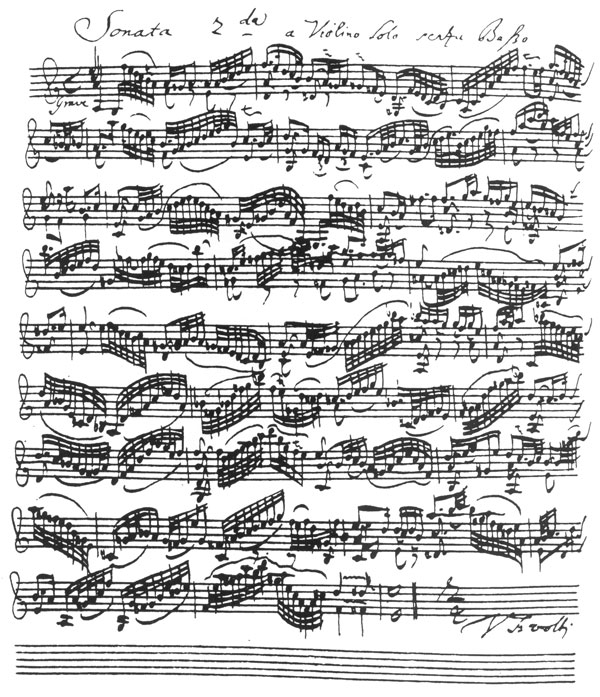

"Exploring the Universe" was written by Kolb in 1987 for Microverse, a compilation of essays about science for non-scientists. The article is the basis of his informative public lectures conveying the wonder and relevance of cosmology for the general public. He has traveled the world, if not yet the universe, giving popular and technical lectures to stimulate in others an interest in the first minutes in the life of our Universe. His lectures incorporate history, art, music, philosophy, humor, and science to communicate an understanding and awareness of the world in which we live.

"Exploring the Universe" was written by Kolb in 1987 for Microverse, a compilation of essays about science for non-scientists. The article is the basis of his informative public lectures conveying the wonder and relevance of cosmology for the general public. He has traveled the world, if not yet the universe, giving popular and technical lectures to stimulate in others an interest in the first minutes in the life of our Universe. His lectures incorporate history, art, music, philosophy, humor, and science to communicate an understanding and awareness of the world in which we live.

Exploring the Universe

"Had I been present at the creation, I would have given some useful hints for the better ordering of the Universe." (Alfonso X, The Wise)

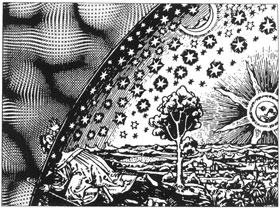

Every thinking person at some time has looked up into the dark night sky and wondered about the Universe. How big, how old? What is it, why is it? Where is the edge, the center? What is beyond, before? Every civilization has imagined answers to these questions, and has employed people expert in such matters to answer them.

Every thinking person at some time has looked up into the dark night sky and wondered about the Universe. How big, how old? What is it, why is it? Where is the edge, the center? What is beyond, before? Every civilization has imagined answers to these questions, and has employed people expert in such matters to answer them.

20th century experts who study such questions about the Universe are scientists known as cosmologists. The word cosmology is derived from the Greek κóσµοζ (COSMOS). κóσµοζ does not mean enormous, immense, Universe, or even "billions and billions." Rather,κóσµοζ is the Greek word for ORDER. Modern cosmologists use physical law as a tool to bring order to an apparently complex and mysterious Universe. The strategy is straightforward: Learn the laws of physics by performing laboratory experiments, and explain the observed Universe on the basis of these laws.

The idea of using our local physical laws as determined by experiments done in terrestrial laboratories to explain the entire Universe did not arise until sometime in the 17th century. The most famous person to try this revolutionary approach was Isaac Newton. Everyone knows that Newton "discovered" gravity, but more precisely, Newton discovered the law of gravity, which states that the gravitational force between two objects is proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them. This law of gravity was confirmed in the laboratory by the famous experiments of Henry Cavendish. Newton made an even greater discovery than the law of gravity-he discovered the universality of gravity. Newton realized that the force responsible for an apple falling on his head was also responsible for the motion of the moon about the earth and the planets about the sun. He conceived of gravity as a universal phenomenon. Newton discovered that the forces responsible for the motions of the planets are capable of human comprehension and that they can be studied in terrestrial laboratories; this is an example of the connection between the "Inner Space" of the laboratory and the "Outer Space" of the cosmos. With a single sweep of genius, Newton freed celestial mechanics from the belief that crystal spheres, mechanical gears, and other sundry devices moved the planets. Is there anyone who can fail to appreciate the simplicity and beauty of the Newtonian view of the solar system? Many of his contemporaries complained that he had removed the hand of God from the heavens. I say he replaced a toilsome hand of brute force with a sublime hand of beauty.

Newton's realization in 1687 that heavenly forces are comprehensible on the basis of local physical law led to a revolution in thought as far-reaching as the revolution caused by Copernicus' realization in 1543 that the sun rather than the earth is the center of the solar system.

The task before the modern cosmologist is the same faced by Newton: understand the laws of physics and apply them to the Universe. Before undertaking this task, let us take a quick look at the Universe.

Building A Universe

"[The Universe] is an infinite sphere whose center is everywhere, its circumference nowhere." (Blaise Pascal, Les Pensees)

What is the Universe made of? A simple answer might be that the Universe is made of three things: Matter, Energy in the form of radiation, and Space. General relativity connects the three on local and universal scales, and it is impossible to study one without the others.

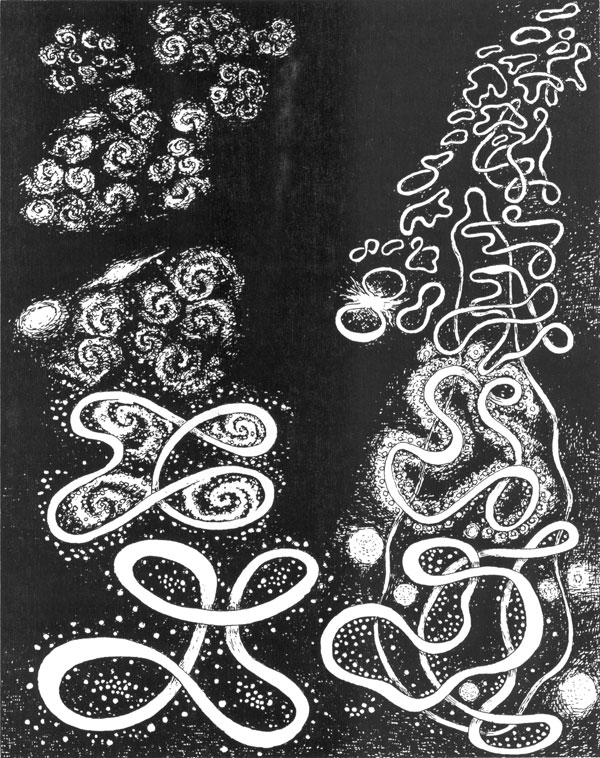

• 1) MATTER: Cosmology is the study of the origin and large-scale structure of the Universe. Here, large means sizes larger than a galaxy. What does matter look like? How is it distributed in space? Galaxies are basic building blocks for cosmologists. Some cosmologists (undoubtedly frustrated botanists) spend their lives observing galaxies and categorizing them by class (spiral, elliptical, irregular, and so on) and subclass. Since the stars we see in the Universe are in galaxies, we must understand why there are galaxies and why they take the shapes and sizes they do. Although we have a qualitative theory of galaxy formation, the answers to such questions await a better understanding of the early Universe.

Galaxies are not the only structures in the Universe. In the past few years a new richness has begun to emerge. It is becoming clear that there are structures in the Universe larger than galaxies. Some galaxies seem to be grouped into larger objects known as clusters. These clusters of galaxies may be part of still larger groups known as superclusters. There is also evidence for giant voids in the Universe, regions free of visible galaxies. These voids seem to form enormous dark bubbles surrounded by a thin film of galaxies. We are able now to notice only the vague outlines of these structures, a hundred megaparsecs in size, illuminated by thousands of galaxies.

In the excitement of discoveries about the large-scale structure of the Universe, we should not lose sight of the fact that the most significant feature of the distribution of matter in the Universe is not its structure, but its lack of structure: its smoothness. The situation is analogous to an ordinary cloud. On small scales there is substructure to a cloud: atoms, water molecules, and water droplets when viewed on progressively larger scales. However, on scales much larger than the distance between water droplets the cloud appears as a smooth distribution of matter. The same is true of the Universe. On scales much larger than the typical distance between galaxies, say a dozen megaparsecs or so, the substructure is unimportant and the Universe appears as a smooth distribution of matter.

The study of a smooth Universe might sound boring, but smoothness has important implications. A Universe that is smooth is said to be homogeneous and isotropic. A space is homogeneous if it is the same at every point, and it is isotropic if it appears the same in every direction. If our Universe is homogeneous and isotropic, then we are led to the profound conclusion that we do not have a privileged view of the Universe. The Universe would appear the same to any observer living in any galaxy. If the Universe is smooth, there is no special place in the Universe, no boundary, no center.

So far we have assumed that we can "see" all the matter in the Universe. What we see is the light from stars, but there is no certainty that all matter is in stars. In fact, there is evidence that most of the mass of a galaxy is not in the form of stars. We can 'weigh' a galaxy just as we can weigh the sun. We determine the mass of the sun by measuring the rotational velocity of the earth about the sun, and we determine the mass of a galaxy by measuring the rotational velocity of stars about the center of a galaxy. The larger the mass of a galaxy, the faster the rotational velocity. When the mass of a galaxy is determined in this way, we find almost 10 times more than can be accounted for by the stars. There seems to be a large amount of DARK MATTER in galaxies. This dark matter is not visible, hence its name. Not only is dark matter found in galaxies, but it is found in galaxy clusters as well. The nature of the dark matter is uncertain; we only know that it does not "shine" in any part of the electromagnetic spectrum. Perhaps dark matter is undetectable because it is not ordinary matter made of neutrons, protons, and electrons, but rather some undiscovered, weakly interacting massive particle. The possibility that the nature of most of the mass of the Universe still awaits discovery is a sobering thought.

• 2) RADIATION: Most of the radiation in the Universe is not in visible wavelengths, but in the invisible microwave region of the spectrum. In 1964, using a Bell Laboratories microwave communications antenna in Holmdel, New Jersey, Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson discovered that our Universe has about 400 photons per cubic centimeter with wavelength of about 1 millimeter. If your eyes were sensitive to these microwave photons, they would "see" about 10(10); microwave photons per second pass through them. This is about 1000 times the flux of optical photons averaged over all the Universe.

The microwave background radiation permeates all of space. Even in the recesses of intergalactic space, there are 400 microwave photons in every cubic centimeter. These background photons have an intensity and spectrum like that of a thermal source of 2.75 degrees Kelvin. The temperature of the Universe between the galaxies is not zero, but 2.75 K. The microwave photons are the oldest things ever detected. They are a fossil of the Universe from long before stars and galaxies ever formed.

The microwave background radiation permeates all of space. Even in the recesses of intergalactic space, there are 400 microwave photons in every cubic centimeter. These background photons have an intensity and spectrum like that of a thermal source of 2.75 degrees Kelvin. The temperature of the Universe between the galaxies is not zero, but 2.75 K. The microwave photons are the oldest things ever detected. They are a fossil of the Universe from long before stars and galaxies ever formed.

The microwave background provides further evidence for the smoothness of the Universe. The microwave radiation reaches us from all directions, and the radiation is the same in all directions to better than one part in a thousand. The only measurable departure from perfect isotropy is caused by the random motion of our galaxy toward the Virgo constellation at a velocity of 600 km/sec (1.35 million miles/hr). The isotropy tells us that when the microwave photons last scattered off the matter, the Universe was very smooth.

• 3) SPACE: The homogeneity and isotropy of matter and radiation must be reflected by the homogeneity and isotropy of space because according to Einstein's theory of gravity, the curvature of space is related to matter. The homogeneity and isotropy of the Universe is so important that it has been elevated to the status of a principle, known as the Cosmological Principle. The Cosmological Principle states that there is no unique or special place in the Universe, e.g., there is no center, no edge, and no preferred location.

Whatever its geometry, the Universe is expanding. The expansion of the Universe was discovered in 1929 by Edwin Hubble. This discovery, the greatest of 20th century astronomy, was made by studying the spectra from distant galaxies. It was known before Hubble that spectra from distant galaxies were not quite identical to laboratory spectra. When the spectrum from a distant galaxy was examined in detail it was found that the wavelength of each line in the spectrum was slightly longer (redder) than the wavelength measured on earth. Hubble discovered the connection between the amount of this red shift and the distance to the galaxy. He noticed that the red shift of the lines increased in direct proportion to the distance to the galaxy.

The study of the building blocks of the Universe has led to two important conclusions. The first, the Cosmological Principle, resulted from the revolution that Copernicus initiated. The second, the expansion of the Universe, was discovered in 1929, and was completely unanticipated.

The Cosmological Principle has profound implications. Whatever our place in the Universe, it is not a special location. We now know that the solar system is not the center of our galaxy, and our galaxy is not the center of the Universe. Our galaxy is not even at rest with respect to the microwave background radiation. Perhaps the discovery of dark matter is the inevitable culmination of the Copernican revolution: Not only do we not occupy a special place in the solar system, the galaxy, or the Universe, but the neutrons, protons and electrons that make up our body are but a small part of the total mass of the Universe, and most of the mass is invisible to us.

The Big Bang

"For violent fires soon burn out themselves." (William Shakespeare, King Richard II)

The Universe is expanding and is full of radiation. These two observed facts are the cornerstones of the theory of the big bang. If the distance between points in the Universe is increasing, then in the past the distance was smaller and the Universe was denser. Just as a gas cools upon expansion and heats upon compression, the temperature of the Universe changes. The Universe is expanding and cooling, so when the Universe was younger it was hotter and denser. At the time of the big bang, the temperature and density were infinite.

In order to comprehend the present state of the Universe we must understand the origins of the Universe. What hope do we have of discovering what the Universe was like 13.6 billion years ago? Well, we can follow the lead of Newton and take physical law as our guide. After all, in the 17th century people asked Newton what hope he had of explaining the motion of distant planets. Extrapolation of knowledge over great time and distance is possible if we understand the nature of physical law under the conditions encountered. Where the physics is simple, or at least understood, predictions can be made. For instance, the temperature on Mars next week can be predicted with greater precision than the temperature in Cleveland. Although Mars is distant, the physics of Martian weather is not complicated by the turbulence of a thick atmosphere.

Earlier than a second after the bang, the Universe was hot and dense enough to produce all particles in copious numbers, even those particles with the most feeble interactions known, the neutrinos. These primordial neutrinos should have survived the big bang and be present today in the form of an undetected sea of neutrinos. The big-bang model predicts that in every cubic centimeter of space there are about 100 of each species of neutrino (100 electron-neutrinos, 100 muon-neutrinos, and 100 tauneutrinos). These invisible weakly-interacting particles may, in fact, be the most significant in the Universe. If a species of neutrino has a mass as small as 100 millionth of the mass of a proton, the lowly neutrino could be the dark matter in the Universe, and the weak shall dominate the Universe. In laboratories around the world physicists are attempting to "weigh" neutrinos to see if they might be the dark matter.

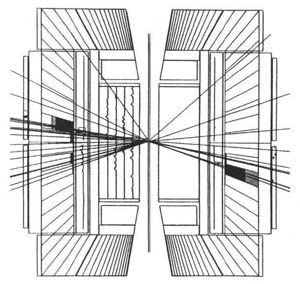

How can we hope to reproduce the very early Universe? Every day, in a handful of particle accelerators throughout the world, scientists accelerate protons or electrons to tremendous energies and collide them. In these collisions we can recreate for a brief moment the conditions that existed in the Universe 13.6 billion years ago. By studying the properties of elementary particles in high-energy collisions we can gain insight into the origin of the Universe in the same way laboratory experiments of the 17th century measured the gravitational force and led to insight into the motion of the planets.

The highest-energy collisions we can study in the laboratory have an energy equivalent to 10(16) K. This was the temperature of the Universe about 10(-12) sec after the bang. At this point our direct knowledge of the properties of matter ends, and hence we are able only to speculate about the Universe at earlier times. To extend the frontiers of knowledge of early cosmology, it is necessary to achieve a deeper understanding of the fundamental forces.

Newton shaped 17th-century cosmology using the force of gravity. We now know that gravity is not the only force at play in the cosmos. In the 20th century we have identified four fundamental forces: gravitational, electromagnetic, weak, and strong. Most people are aware of the influence of the gravitational and electromagnetic forces. The less familiar strong and weak forces are just as crucial to our existence. The strong force is responsible for the nuclear interactions that bind neutrons and protons into nuclei and that bind quarks and gluons into neutrons and protons. The weak force is responsible for the transmutation of protons into neutrons. It is the action of the strong and weak forces in the sun that causes four protons to form a helium nucleus consisting of two neutrons and two protons, thereby releasing energy to power the sun. Our Universe is shaped by an interplay of all four fundamental forces.

Although the four forces are fundamental, they may be related. There is historical precedent for the unification of seemingly disparate forces. Until the end of the 19th century it was believed that magnetic forces were distinct from electric forces. The pioneering work of Faraday and Maxwell in the last century demonstrated that electric and magnetic forces are different manifestations of a single fundamental electromagnetic force. This interplay of electric and magnetic phenomena is apparent every time you turn on an electromagnetic motor. In the 1960's, Glashow, Weinberg, and Salam demonstrated that the electromagnetic and weak forces are related, and in fact are different aspects of a single electroweak force. Many particle physicists feel that unification is the path to deeper understanding, and that all four fundamental forces are different aspects of a single force.

Unification of the forces has important implications for the early Universe. Unification theories predict that at very high temperature the character of the fundamental forces is different from what is now observed. For instance, the strength of the electromagnetic force between two particles is observed to decrease in proportion to the square of the distance between them (like the gravitational force), while the strength of the weak force between two particles is seen to decrease much faster with separation. At high temperature, however, electroweak unification predicts that the weak force should behave exactly as the electromagnetic force. According to unification theories, as the Universe expanded and cooled the behavior of fundamental forces changed in a series of transitions. The transition of the electroweak force, according to unification theory, should have occurred around 10(-12) sec after the bang. This electroweak transition is perhaps the last event in a series of unification transitions, the first of which occurred 10(-43) sec after the bang when the "super" unity between the gravitational force and the other forces were lost. Then, at 10(-35) sec the "grand" unity between the strong and electroweak forces was lost. Finally, at 10(-12) sec the weak force split from the electromagnetic force.

One exciting prediction of unified theories is that the unification transition may not have occurred everywhere, so there might be regions of the Universe where the fundamental forces still retain their high temperature character. An example of such a region is a cosmic string. A cosmic string is a very long, very thin region of space where fundamental forces have different properties. Strings produced in the grand unification transition might be present today as loops of string that are megaparsecs in radius but only 10(-28) cm thick. Cosmologists and particle physicists are still trying to understand the consequences of cosmic strings. One striking feature of a string from the grand-unification transition is that it would weigh more than a million-billion tons per centimeter. A string only a few centimeters long would contain the mass of a mountain! Another interesting characteristic of such strings is that they can turn matter into antimatter. A proton passing through a cosmic string can turn into an antiproton. Other bizarre features of cosmic strings are just now being explored.

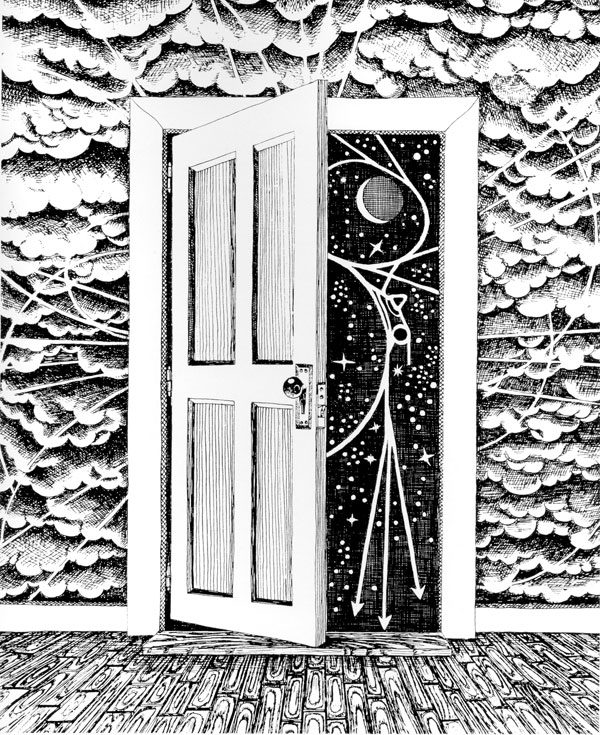

An exploration of the earliest moments of the Universe requires an understanding of the nature of the fundamental forces. It is through recreating the conditions of the early Universe in high-energy collisions at accelerator laboratories that we can learn the fundamental forces at work and unlock the secrets of the Universe.

Epilogue

"The Universe is full of magical things, patiently waiting for our wits to grow sharper." (Eden Phillpotts, A Shadow Passes)

This attempt to paint a simple, beautiful picture of the Universe is based upon the big-bang model. We have direct confirmation, in the form of the abundance of primordial hydrogen and helium, that our model of the Universe worked as early as 1 second after the bang, some 13.6 billion years ago. We can use the Inner Space/Outer Space connection and apply the knowledge we learn in the laboratory to stretch our knowledge about the Universe back to 10(-12) sec after the bang. We seem to be on the verge of understanding a crucial transition in the Universe, the electroweak transition.

Where should the story end? If we have a consistent picture of the Universe for the last 13.6 billion years, back to a second after the bang, is that enough? No, I think we won't stop asking fundamental questions about the Universe until all the answers are in hand.

The 500th anniversary of Columbus' voyage of discovery has focused attention on the boldness, imagination, and courage of the explorers of our world. Today, the spirit continues in a new age of discovery. No longer do we explore the earth by sailing the sea in caravels and navigating by the light of the stars. We now discover the heavens by riding the vessel of our imagination, steering by the light of the discoveries at telescopes and accelerators.

I often wonder what people in the next century will think of our explorations. Will they regard our ideas of grand and super unification with the same amusement with which we look upon the efforts of previous centuries, and think them naive? However they judge our scientific efforts, I believe that they will not judge us to have been lacking in boldness and imagination as we again attacked problems once thought to lie outside the realm of human comprehension.

Finally, what are we to make of our place in the Universe? Have the discoveries that seem to push us further from our once presumed privileged position in the Universe made us inconsequential? No, I think the opposite is true. The fact that on a small planet, orbiting an average star, in a distant spiral arm of just one of countless galaxies in a possibly infinite Universe, we look out into the dark night sky, not in fear, but with a determination to comprehend the enormity of what we see, makes us more special than living in a privileged position ever could. Perhaps this feeling is best expressed by poets:

The Brain-is wider than the Sky

For-put them side by side-

The one the other will contain

With ease-and You-beside

The Brain is deeper than the sea

For-hold them-Blue to Blue

The one the other will absorb

As Sponges-Buckets-do

Emily Dickinson, 1862

Thanks

Sue Grommes ● Adrienne Kolb ● Rocky Kolb ● Bruce Chrisman

John Peoples ● Robert R. Wilson ● Leon M. Lederman ●

S. Chandrasekhar

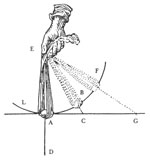

Leonard Euler's Illustrator ● Angela Gonzales ●

Pablo Picasso

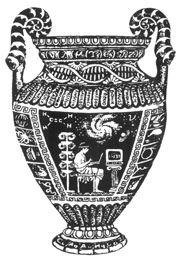

East Indian Mythology ● 5th Century B.C. Athenian Vase

Painters and Potters

Hans Bethe ● Fermilab Photography ● Al Johnson

John Keats ● Emily Dickinson ● Jean Lemke ● Marcel Proust ●

Chocolate

Lillian Hoddeson ● William Shakespeare

●

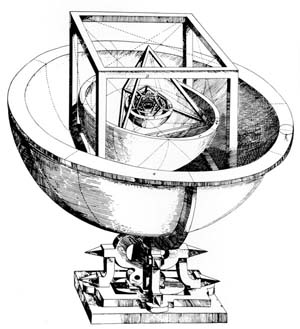

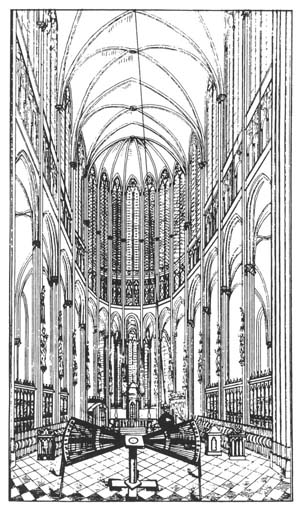

19th Century Illustration Depicting a Mechanical Universe

5th Century B.C. Greek Mythology ● Leonardo da Vinci

This publication was selected from the treasures of the Fermilab Archives.

![]()