NuMI Gets Rolling

With the first installment of DOE funds, NuMI moves from proposal to bona fide project.

Neutrinos, those antisocial particles that refuse to interact with anything, are streaming all around—and through—us, but we know very little about them.

That may soon change, however. On October 13, President Clinton signed the appropriations bill for the U.S. Department of Energy, allocating $5.5 million in fiscal year 1998 for Fermilab’s Neutrinos at the Main Injector collaboration and making NuMI no longer just a proposal but a bona fide project. If funding holds up over the next several years, experimenters hope to begin taking data sometime in 2002.

And then perhaps we’ll know whether neutrinos have mass.

COSMOS and MINOS

According to Gina Rameika, project manager for NuMI, the $5.5 million will pay for engineering and design work on the 1.2-kilometer tunnel that will house the NuMI beamline.

Two experiments are planned for this new beamline. Both are designed to test whether neutrinos oscillate—or change from one kind, or flavor, to another—and hence have mass.

One is called the short-baseline experiment, “short” because the distance from the source of neutrinos to the proposed detector, COSMOS, is only about one kilometer. Experimenters will direct a nearly pure beam of muon neutrinos at a target and look for oscillation between the muon and the electron neutrinos. These are the neutrinos that some physicists believe may account for some of the dark matter, the bulk of matter in the universe that astronomers are unable to see but know exists.

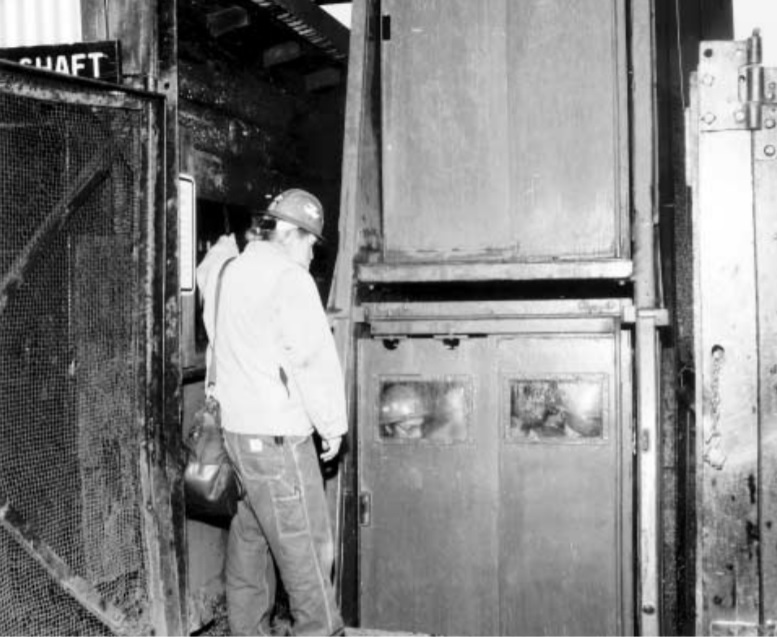

The other experiment is called the long-baseline experiment, “long” because the target is 730 kilometers away, in a former iron mine in Soudan, Minnesota. The Soudan mine is now an underground state park run by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. It also houses a giant one-kiloton detector (called Soudan 2), which has been used to search for evidence of proton decay and now is involved in studies of atmospheric neutrinos.

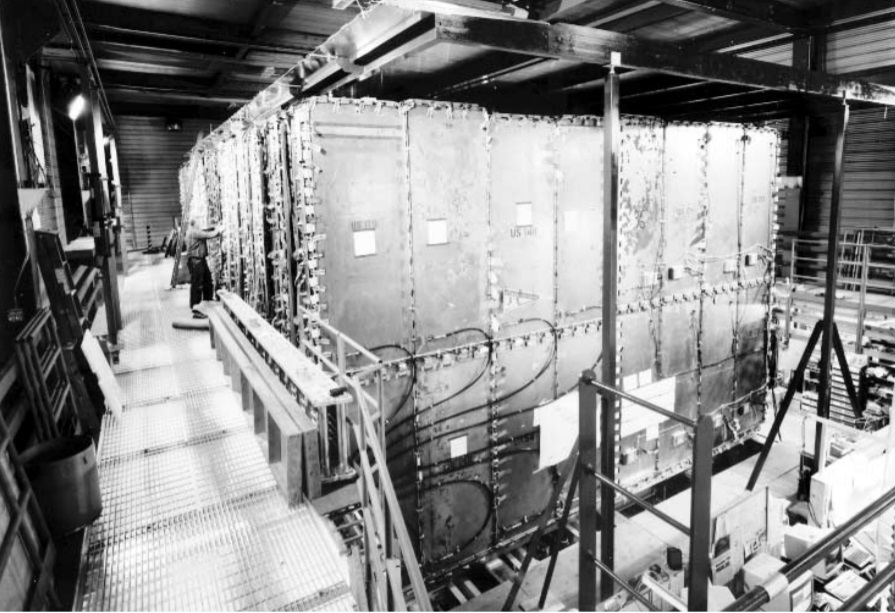

For this experiment, two very similar MINOS detectors will be used, one placed at the end of the beamline on the Fermilab property and a larger one in a proposed hall in the Soudan mine. Experimenters will compare the properties of the neutrinos as they leave the Fermilab site and when they arrive in Soudan, counting at each site the number of electron, muon and tau neutrinos. If electron or tau neutrinos appear at Soudan, the experimenters will know that the neutrinos oscillated, and that neutrinos therefore have mass.

Construction and bats

The $5.5 million gets NuMI started, but funding is critical to keep the project moving on schedule. According to Rameika, civil construction of the tunnel here and of the cavern at the Soudan mine is slated to begin in fiscal year 1999, in winter or early spring. The bulk of construction work for the detectors should take place in fiscal year 2000. By fiscal year 2001, experimenters hope to get what is called “beneficial occupancy” of the Fermilab tunnel and the Soudan hall, allowing installation of the detectors and beamline components, a process that takes about a year. Finally, Rameika said, “the goal is to begin commissioning [turning the beamline on and getting the detectors working] in late fiscal year 2002.”

But first, excavation of the tunnel here at Fermilab is waiting for DOE’s budget for fiscal year 1999.

And construction of the hall in the Soudan mine is waiting for a requested $3 million from the University of Minnesota.

Construction in Soudan may also have to wait for the Little Brown Myotis bats that live in the 54 miles of tunnels in the former mine. According to Bill Miller, manager of the underground Soudan 2 lab, this is the largest bat habitat in the upper Midwest. Bats from as far as 250 miles away come to roost in the Soudan’s caverns.

Trouble is, the bats begin hibernating in September, and finally rouse themselves at the end of April. If construction should begin during that time, the bats might wake and fly to some quieter place, meanwhile using up too much of their stored food supplies to survive the winter. They could very well die.

One solution is to begin construction between May and August. That way, the bats will find another roosting spot before any damage is done.

But even if construction needs to begin earlier, Miller claims there shouldn’t be a problem. Just make a lot of noise in September before the bats settle down to sleep.

And how does Miller propose generating noise? Set up a stereo system, he said, and “play something obnoxious like heavy metal.”