Cathedrals and Accelerators

In his film The Creation of the Universe, Timothy Ferris noted some striking analogies between cathedrals and particle accelerators:[1]

Cathedrals achieve soaring heights in space, and accelerators achieve soaring heights in energy.

Cathedrals and accelerators represent major investments for the countries that build them. For example, Ferris noted that France in the 14th century spent a larger fraction of its wealth on cathedral construction than the USA spent in the 1960s to send astronauts to the Moon.

As major collective enterprises, a cathedral or an accelerator forms an expression of the ideals and vision of the culture that constructs it.

Cathedral or accelerator construction brings together the best talent in the land, pushing skills and technologies to their limits. Witness the development of the Gothic arch and flying buttress; or the vacuum systems that made the first Crookes tube possible, leading eventually to the Fermilab Tevatron with its superconducting magnets. Such advances enlarge the envelope of the possible!

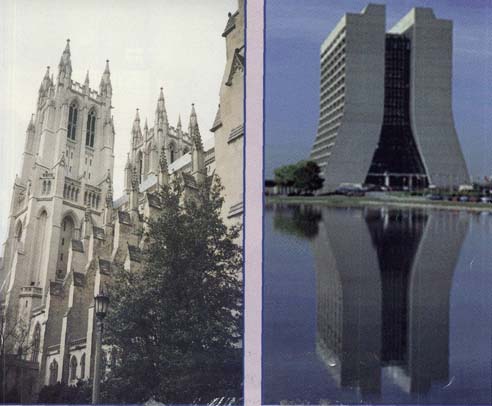

An accelerator pushes one's thoughts outward, to model physical structures and interactions beyond the scale of our everyday experience. A cathedral lifts one's thoughts upward, to meditate upon the spiritual dimension of life and see beyond oneself. Accelerators are proud monuments to what we can know despite the finiteness of our minds. Cathedrals recall us to a spirit of humility, reminding us of greater mysteries that cannot be placed between the microscope slides of science. The accelerator and the cathedral offer complementary tools for appreciating existence: accelerators, to reduce the physical world to its fundamental parts; cathedrals, to integrate our existence holistically into a picture of purpose and meaning, Robert Wilson, the first Director of Fermilab, captured a resonance between these complementary needs in his design of the laboratory's office building, now called Wilson Hall, which was inspired by Beauvais Cathedral.[2]

There seems to be precious little public interest in physics. But the interest is very real; we simply don't know how to engage it effectively. The latent public interest presents itself on two fronts: (1) the practical curiosity to know "how things work," and (2) a deep fascination for the cosmic questions such as the origin of the universe, our place in time and space, and whether we are alone in the universe.[3] In both the practical and cosmic questions, we pass back and forth between the accelerator and the cathedral.

Daily life has been dramatically changed through the inventions of applied physics. Modern life with radio communication, networked computers, lasers, automobiles, jet planes, and non-invasive medical imaging forms a striking contrast to the grind of daily routine in medieval times.(4) Of course, the applied physics of the catapult or the hydrogen bomb also stand as reminders that the applications of the physicist's discoveries need the kind of moral guidance that one expects to be taught in cathedrals.

Physics has shaped our knowledge of the human condition by illuminating the cosmic questions. In the matter of origins, for example, the big bang cosmology provides detailed insight into physical mechanisms, complementing the meaning questions addressed by philosophy and religion. Unfortunately, such complementarity has often and unnecessarily been seen as a conflict. A famous example arose in the trial of Galileo. That unhappy story has now reached a brighter conclusion. On November 10, 1979, Pope John Paul II commemorated the centennial of Albert Einstein's birth by proposing that the Roman Catholic Church re-examine Galileo's case. Thus in 1983, on the occasion of the 350th anniversary of the publication of Galileo's Dialogues Concerning Two World Systems, the Pope established a special Galileo Commission, stressing that through "humble and assiduous study" the Church should undertake to "dissociate the essentials of faith from the scientific system of a given age." A year later, in a formal statement the Vatican announced that "the Church had erred in condemning Galileo."(5)

One of John Paul II's biographer's notes that "Galileo's vindication after three and a half centuries was an unprecedented breakthrough in the history of the Church, but to John Paul II it represented only the first step in a much broader effort to establish a dialog between religion and modern science."(6) In a 1988 papal letter, the Pope said, "While [science and religion] can and should support each other as distinct dimensions of a common human culture, neither ought to assume that it forms a necessary premise for the other."(5) The 1984 Galileo statement, plus the ongoing publication of research by the Vatican observatory, the triennial science conferences hosted by the Pope, and his recent announcement that 'Today ... new knowledge leads to recognition of the theory of evolution as more than a hypothesis,"(7) represent serious steps to make good the attempt at dialog.(8) But large developments grow from small beginnings.

In 1953 a young Polish priest named Karol Wojtyla went on several skiing, hiking, and kayaking outings with a small group of friends. Two of the young priest's friends happened to be nuclear physicists. Although Karol Wojtyla had not been formally trained in science, one of the physicists, Jacek Hennel, recalled later that in their conversations the young priest kept trying to relate scientific topics to moral and ethical ones.(9) This was the approach Father Wojtyla would consistently apply as priest, bishop, and cardinal, and finally as Pope John Paul II, when he had to deal officially with issues of cloning and cosmology.

Not only are physicists and priests interested in the cosmic questions: so are children and parents, so are butchers, bakers, and candlestick makers. While relatively few are trained to solve differential equations or collect spectroscopic data themselves, all are interested in the larger issues that are shaped by such activities. This suggests a vision for physics which we Sigma Pi Sigma members can help implement, because we form a unique physics "alumni association."(10) The vision sees physics not only as a purveyor of technology, but, in addition, recognized as a vital liberal art, shaping community and culture. Who knows the potential within a child who asks if space ever ends, and receives a humble but knowledgeable response from someone who loves both children and physics! Who can measure the long-term benefits from the personal bridges that are built between the Jacek Hennels and the Karol Wojtylas? Each opens an important window onto the universe, and through thoughtful dialog fit their pieces of the picture together into a coherent whole!