Fermilab Fosters Technology Transfer

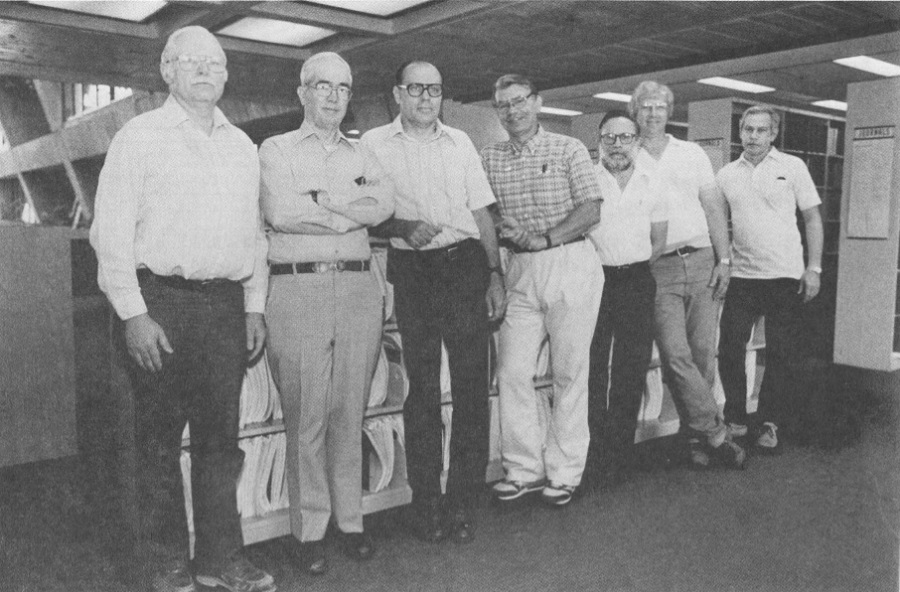

Some Fermilab patent holders (left to right) Quentin Kerns, Bill Fowler, Carl Pallaver, Frank Cilyo, Carl Lindenmeyer, Frank Juravic, and Ken Bourkland.

Fermilab is a leader in particle physics with the most powerful accelerator in the world that is also the only superconducting synchrotron in operation. Fermilab is also a leader in high technology. Construction and operation of the Energy Doubler has brought superconductivity from the laboratory work bench to the threshold of an industry. The momentum of the Doubler construction did much to stimulate the modern superconducting wire industry. At the same time many developments were perfected for cryogenic refrigerators and controls. As applications of accelerators increase, people look toward Fermilab for expertise in all fields, such as beam dynamics, rf magnet systems, and controls. Electronic systems devised at Fermilab are finding important applications outside the field of high-energy physics. Some of the modules pioneered here have become commercially available. Since 1980, Fermilab's involvement in technology has also been consistently recognized with seven prestigious IR-100 awards.

There are still problems with taking technology developed at Fermilab and moving that technology out to users in industry and government. Fermilab is a single purpose national laboratory. Our basic mission is research in elementary particle physics and construction and operation of the accelerators and laboratory facilities necessary to carry out that research. It is not appropriate to compare Fermilab to a multi-purpose national laboratory like Argonne where a wide spectrum of different projects are underway including many that bear directly on problems in the industrial sector. Nevertheless, there is cause for reflection when the relative patent rates at Fermilab are compared to some other laboratories. For example, the patent rate at Brookhaven National Laboratory is something like ten times higher than that at Fermilab. The rate at Bell Laboratories may be as much a s one hundred times higher. This difference in patent rate gives rise to the suspicion that some good Fermilab technology ideas may not be getting all the visibility that they deserve.

Patents are not the sole means of transferring technology. Fermilab's impact on the superconducting industry is well documented. Part of this comes about through the give-and-take of interaction with commercial vendors working with Fermilab. Only a few patents touch on this tremendous area of superconductivity technology that has been developed here.

In the last few years there has been an increasing national emphasis on technology transfer. In 1980, Adlai Stevenson of Illinois, was a sponsor of a law encouraging national laboratories to move their technology out into the private sector. At about the same time, Leon Lederman established the Fermilab Industrial Affiliates as a mechanism for facilitating this kind of transfer. Recently another law (Byah-Dole) has given patent rights to many universities and non-profit concerns working on federal government contracts. For example, universities with research going on at Fermilab can retain their own patents. This is considerably different than the situation at Fermilab where URA can only get licenses to exploit Fermilab patents on a case-by-case basis. The Department of Energy is now negotiating with the University of Chicago to extend the Byah-Dole privileges to Argonne. The same privilege might eventually by extended to Fermilab.

How does Fermilab identify interesting technology? In the past this has mostly been done either through individual employee awareness of the importance of a particular technology or by watching the publications released by the Laboratory. Each Laboratory publication is screened by the Laboratory patent officer, Dick Carrigan, and a DOE patent attorney. Recently, an incentive has been added to increase awareness of technology. A $50 award will be made for filing a Record of Invention form in addition to the $50 an employee will receive once a patent application is executed.

A Record of Invention form is a one-page standard document available in the Publications Office, WH3E. The form is straightforward, mainly requiring the title of the invention plus a description, and some supporting material about where the invention is first mentioned. The Laboratory also requires that one of the witnesses to the "Record of Invention" be the employee's supervisor. This disclosure should be filed whenever there is some reason to feel that a new technology developed at the Laboratory may be patentable. Basically, employees should take an optimistic view of what constitutes patentability. In most cases complex questions concerning patent law should be left to patent lawyers. The Department of Energy has recently made arrangements for a DOE patent attorney to be available on the Fermilab site every Tuesday so that questions can be conveniently answered. It is often easy to convince yourself that some technology is not patentable or is not new. On the other hand, the "Record of Invention" constitutes an important flag to others in the Laboratory about this technology. It also serves as a positive indicator of a person's contribution to the Laboratory. It is often possible to usefully disseminate a technology even though a patent cannot be obtained.

Since 1970, 27 employees have had patents issued, some more than one. The names of the employees and the titles of their patents follow: K. Atac, Quenching Gas for Detectors of Charged Particles; K. R. Bourkland and R. A. Winje, High Current Power Supply for Accelerator Magnets; F. Cilyo, Bidirectional Power Amplifier; J. R. Heim, Low Heat Conductant Temperature Stabilized Structural Support and Method of Eliminating the Training Effect in Superconducting Coils by Post-Wind Preload; H. Hinterberger, A Non-Tracking Solar Concentrator with a High Concentration Ratio and Radiant Energy Receiver Having Improved Coolant Flow Control Means; F. Juravic, Improved Gaseous Leak Detector; C. R. Kerns, Current Level Detector; Q. A. Kerns, Stabilization System for Resonant Cavity Excitation and High Power Radiofrequency Attenuation Device and Q. A. Kerns and H. W. Killer, High Power Radiofrequency Attenuation Device; C. W. Lindenmeyer, Shuttleless Toroid Winder and Locking Mechanism for Indexing Device; A. W. Maschke, An Electrostatic Accelerated Charged Particle Deflector; P. O. Mazur and C. B. Pallaver, Adjustable Expandable Cryogenic Piston and Ring; R. F. Nissen and E. B. Tilles, Resistive Coating of Long Ceramic Tubes and Indium-Sesquioxide Vacuum Gauge; C. B. Pallaver and M. W. Morgan, A Combination Vacuum Pump-Out and Pressure Relief Valve and Cryogenic Expansion Machine; A. Roberts, Image Dissecting Cherenkov Detector for Identifying Particles and Measuring Their Momentum; J. A. Satti, Superconducting Magnet and Method of Constructing a Superconducting Magnet; R. Sheldon and B. P. Strauss, Method for Centering and Restraining Coils in an Electromagnet; B. P. Strauss, A Method of Fabricating Composite Superconductive Electrical Conductors; and B. P. Strauss, P. J. Reardon, and R. H. Remsbottom, Method of Fabricating Composite Superconducting Wire; C. A. Swoboda and A. W. Maschke, High Speed Analog to Digital Converter; P. C. VanderArend and W. B. Fowler, Superconducting Magnet Cooling System; R. J. Yarema, An Apparatus for Controlling the Firing of Rectifiers in Polyphase Rectifying Circuits.

The Laboratory has also established a patent survey group. The group includes M. Awschalom, S. Baker, G. Biallas, R. Ducar, R. Fast, J. Finks, I. Gaines, Q. Kerns, C. Lindenmeyer, P. Mantsch, B. Miller, R. Niemann, T. Peterson, R. Shafer, J. Simanton, and J. Zagel. These people have gone over recent technology development within the Laboratory and compiled a list of 100 areas of technology development. The list is being refined and documentation is being gathered for the technologies. Discussions are also underway on how this technology can be widely disseminated with a number of possibilities under consideration.

Fermilab remains first and foremost a single-purpose Laboratory with a mission to investigate very basic science. But, modern science does spawn technology. Fermilab employees need to be aware of this technology and ways to use it outside of particle physics. It would be nice to find an application for superconductivity with the same impact as microwave technology where every home now needs a microwave oven. A $5 license fee for a superconducting toothbrush from every household in America could make a profound change in the Fermilab budget. In lieu of this windfall, Fermilab can be proud that it has helped to create an entirely new industry in superconductivity with an annual business volume somewhere over a hundred million dollars and a potential for billions.