Cancer Therapy Facility at Fermilab Finds its Place in Modern Health Care

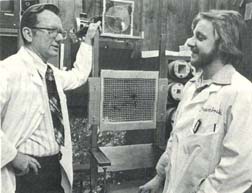

Dr. Frank R. Hendrickson (left) and Brian Pientak, radiation therapy technologist, in the Cancer Therapy Facility at Fermilab. They are in the shielded room in which patients are exposed to neutrons. The patients sit in the chair between them. Just above Hendrickson's left hand is a laser device that technologists use to precisely align a patient with the neutron source

Neutron therapy is becoming an important new technique for bringing certain types of cancer under control. Dr. Frank R. Hendrickson, associate director of the Cancer Therapy Facility (CTF) at Fermilab, told science writers attending a press conference at the joint annual meeting in Chicago of the American Physical Society and the American Association of Physics Teachers.

Also professor and chairman of the Department of Therapeutic Radiology at Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke's Medical Center in Chicago, Dr. Hendrickson said that for certain types of cancer, treatment with neutrons appears to be promising. However, he cautioned the writers about becoming overzealous. The Fermilab facility has been running only since October 1976, not long enough for substantial data to have been accumulated on the long-term effects of neutron therapy on patients, he explained.

Yet, he was optimistic and enthusiastic about neutron therapy. Even though it appears to be effective with certain types of cancer, the results should be thought of as an improvement over standard modes of treatment, not regarded as a breakthrough, he said.

Since the Fermilab CTF opened, more than 600 patients have been exposed to neutrons. The types of cancers that have been treated include those of the salivary glands, advanced head and neck cancers and malignant tumors of the pancreas and brain. These cancers have a tendency to remain localized and less often spread to other parts of the body, thus making them good candidates for neutron therapy. Some of the patients had cancers that were too large to be removed by surgery, or just didn't respond to the standard treatment modes. These include radiation, chemotherapy and surgery.

The average patient at Fermilab gets about six or seven neutron treatments, but range from 2-20 said Hendrickson at the press conference. Some of the treatments may be as infrequent as one each week, and as frequent as three a week. Each exposure lasts only a few minutes.

"In no situation has the treatment been worse for the patient than would have been the standard treatment," said Hendrickson. "Our result in every case has been at least as good."

The facility at Fermilab is capable of treating up to about 50 patients a week, he said. At the present time, about half that number are being seen.

He reminded the science writers that "cancer is the most curable dreaded disease we have. The cure rate is about 50 percent. If the cancer is caught in its early stages, that cure could be as high as 90 percent." It is the leading cause of death in people under 55, he added.

Indeed, therapy with neutrons appears to be an important missing link in the spectrum of treatments available, according to Dr. Hendrickson. Just before his press conference, he addressed the annual meeting on "The Physical and Biological Basis for Neutron Treatment."He showed color slides of some patients with malignant tumor growths of the ear, side of the face and soft palate inside the mouth. After neutron treatment, their recovery was remarkable. From the color slides showing the patients following therapy, only their physician would have known an ugly tumor had once ever deformed their features. It was dramatic visual evidence of the powerful role neutron therapy is gaining in modern health care.

It wasn't always that way. In the 1940's, some work was done with neutron therapy, Dr. Hendrickson told his audience at the meeting. Unfortunately, the mechanism of action and biology of the treatment was not fully and correctly understood. Consequently, the results were less than desirable. So interest in using fast neutrons waned.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, an attempt at using neutrons was started at Hammersmith Hospital in London. With improved understanding and more sophisticated equipment, some of the results were gratifying, he said. From this second cautious beginning, interest spurted and spread to this country and to others throughout the world. In the past 10 years, 4,000 patients have been treated at neutron therapy facilities, most of them in the past few years.

"To date, clinical research has not progressed sufficiently to reach firm conclusions, but the general direction of the observation has paralleled that of the initial work in England," said Dr. Hendrickson at the meeting. "Within the next several years, sufficient followup will have been achieved to reach firmer conclusions."

He also said, "The potential for improvement in the management of cancer patients with radiation therapy has come about from the intense cooperative interaction among the physical sciences, biological sciences and medical sciences.

Without this high degree of precision and indepth understanding of the absorption of heavy particles in various physical materials, the whole program could not have begun."

He concluded his remarks at the annual meeting by saying, "The medical sciences have been able to combine physical and biological research data into clinical research programs that compare the best of the standard treatments with these new frontiers."

And at the press conference, Dr. Jacques Ovadia, chairman of the Medical Physics Department at Michael Reese Medical Center in Chicago and also a speaker at the annual meeting, gave his overview. He said, "Neutron therapy has come of age."

Commercial equipment is available now and hospitals are capable of running the units reliably, he continued. "We are not giving anything away in terms of good patient care by using neutrons," Dr. Ovadia also said.

Dr. Hendrickson added that it will probably be three or four years before patients will be treated with these units.