NOvA Experiment Sees First Long-Distance Neutrinos

Scientists on the world’s longest-distance neutrino experiment announced today that they have seen their first neutrinos.

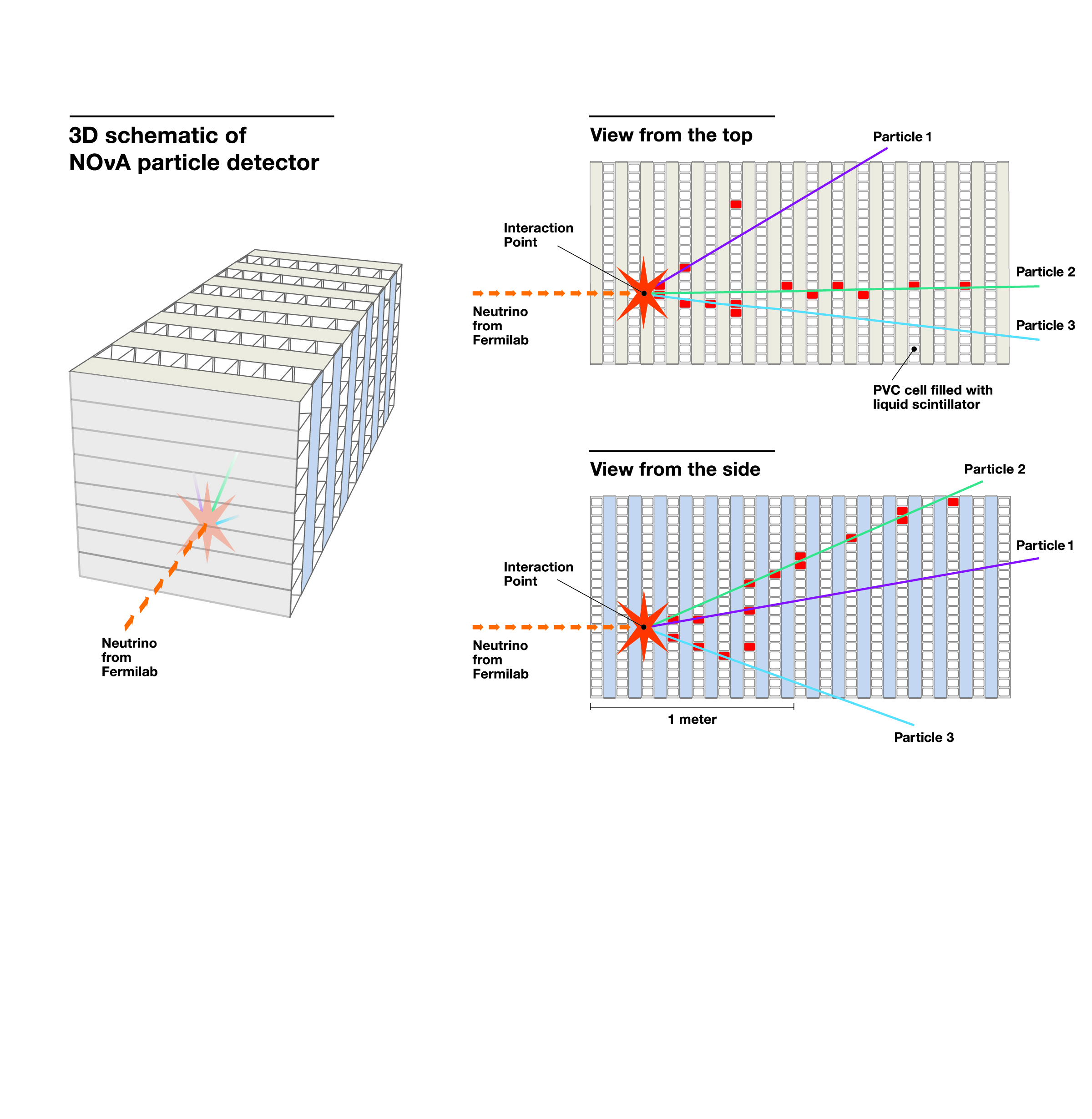

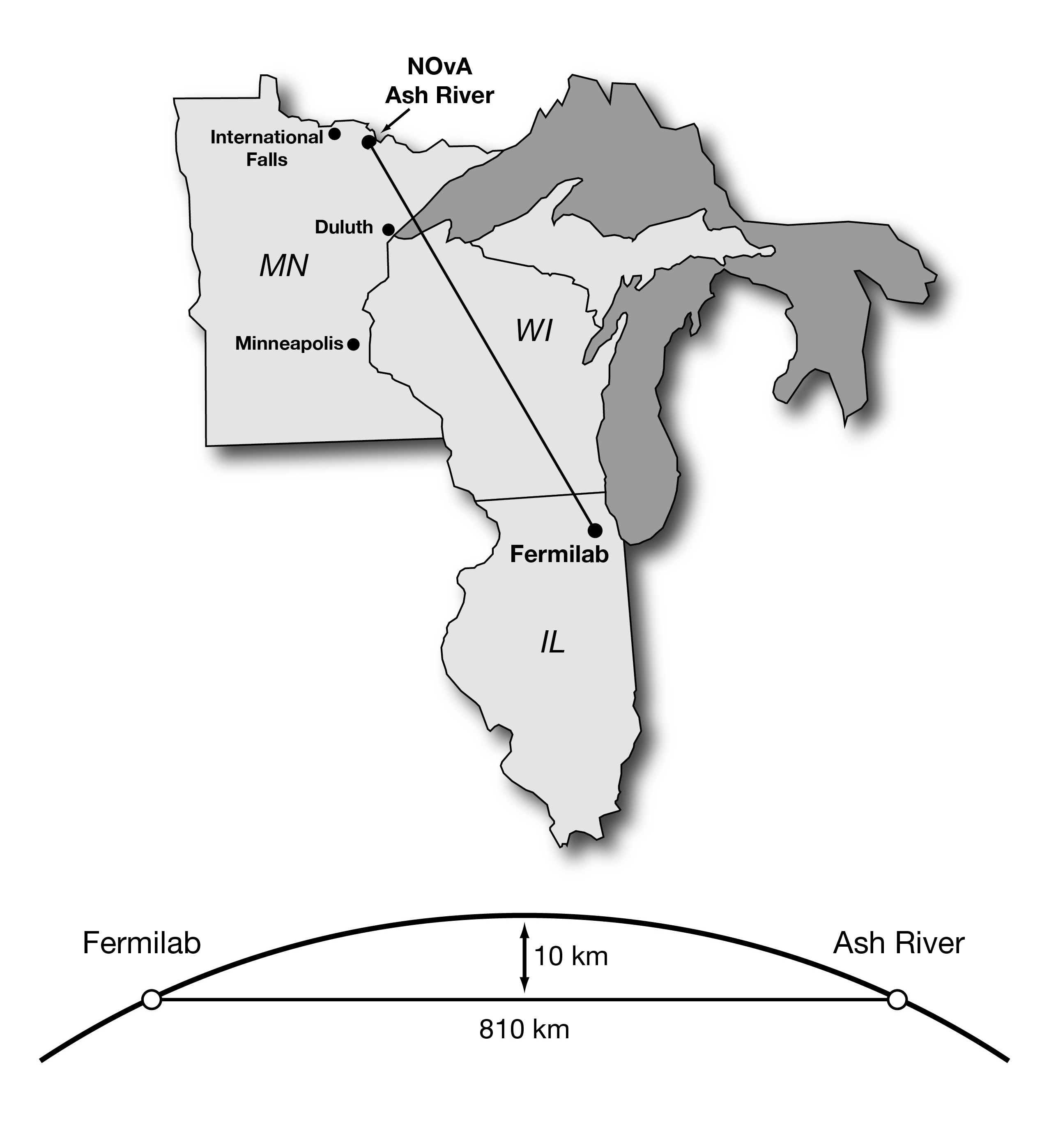

The NOvA experiment consists of two huge particle detectors placed 500 miles apart, and its job is to explore the properties of an intense beam of ghostly particles called neutrinos. Neutrinos are abundant in nature, but they very rarely interact with other matter. Studying them could yield crucial information about the early moments of the universe.

“NOvA represents a new generation of neutrino experiments,” said Fermilab Director Nigel Lockyer. “We are proud to reach this important milestone on our way to learning more about these fundamental particles.”

Scientists generate a beam of the particles for the NOvA experiment using one of the world’s largest accelerators, located at the Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory near Chicago. They aim this beam in the direction of the two particle detectors, one near the source at Fermilab and the other in Ash River, Minn., near the Canadian border. The detector in Ash River is operated by the University of Minnesota under a cooperative agreement with the Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

Billions of those particles are sent through the earth every two seconds, aimed at the massive detectors. Once the experiment is fully operational, scientists will catch a precious few each day.

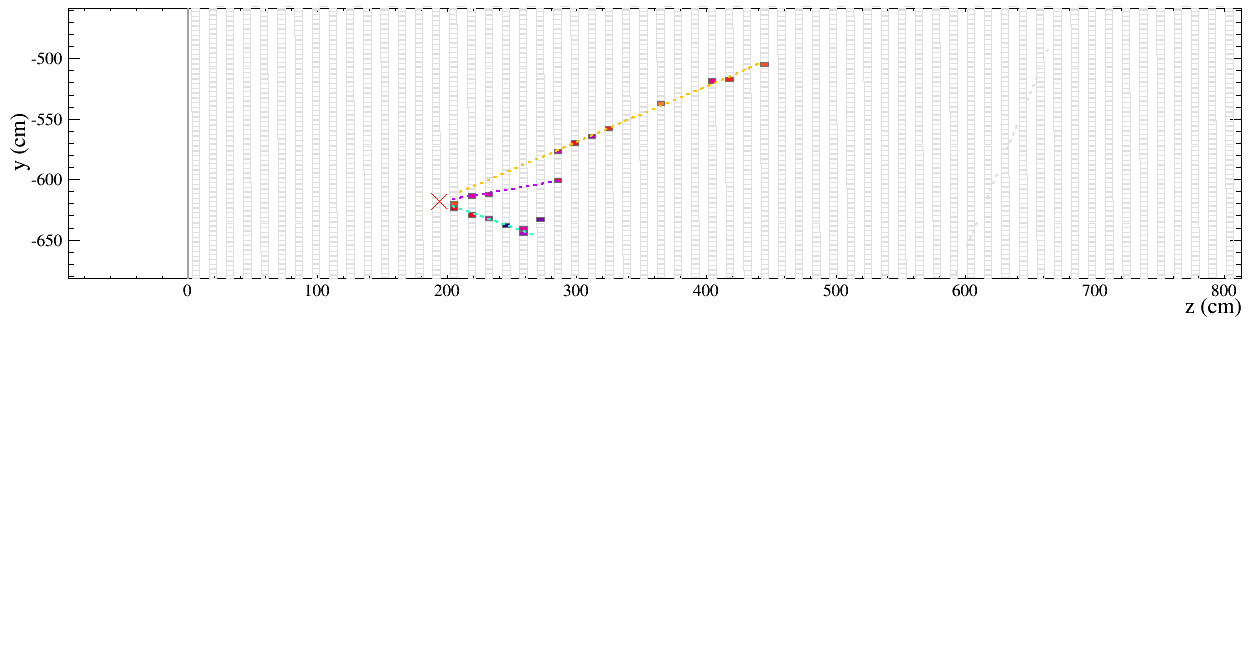

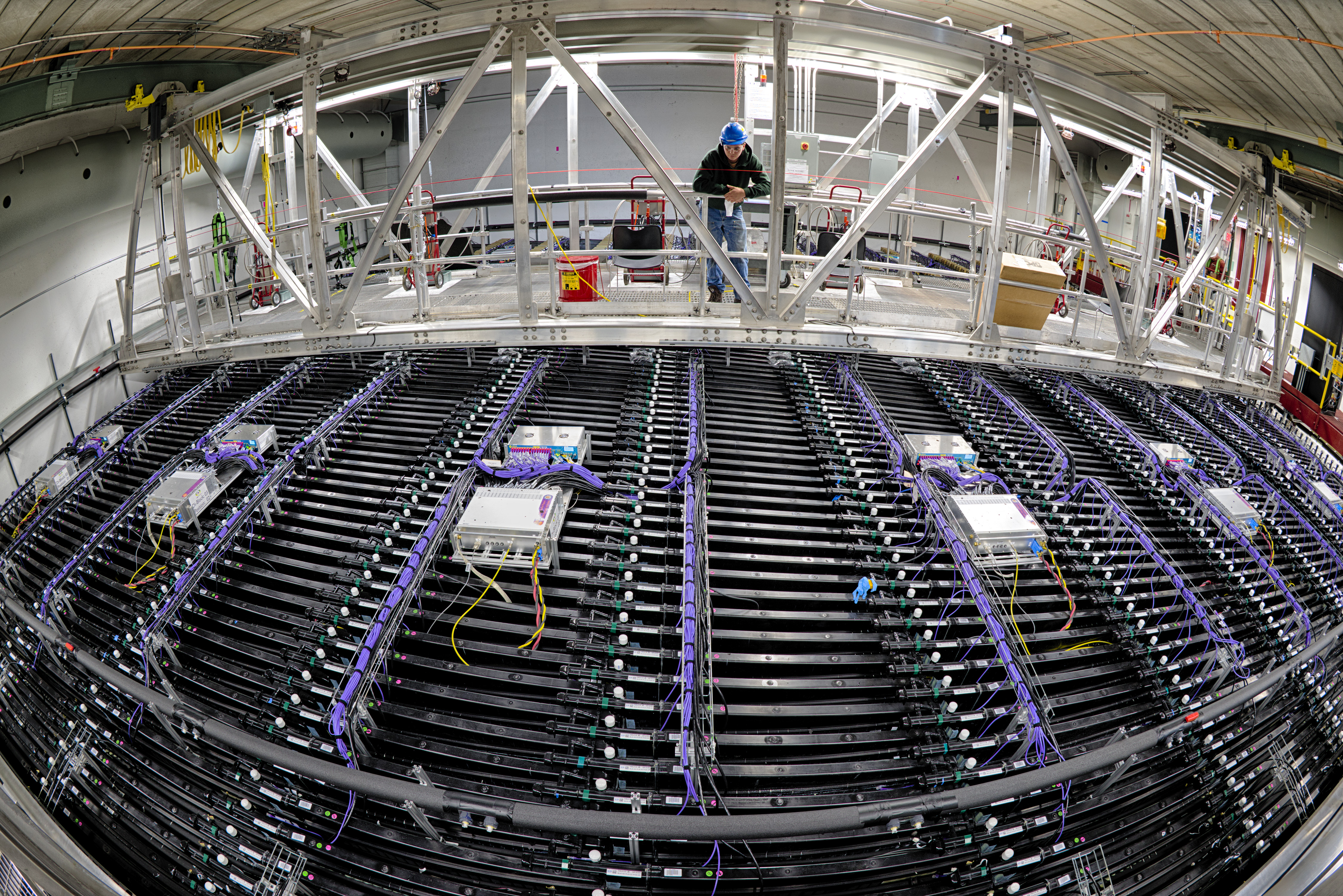

Neutrinos are curious particles. They come in three types, called flavors, and change between them as they travel. The two detectors of the NOvA experiment are placed so far apart to give the neutrinos the time to oscillate from one flavor to another while traveling at nearly the speed of light. Even though only a fraction of the experiment’s larger detector, called the far detector, is fully built, filled with scintillator and wired with electronics at this point, the experiment has already used it to record signals from its first neutrinos.

“That the first neutrinos have been detected even before the NOvA far detector installation is complete is a real tribute to everyone involved. That includes the staff at Fermilab, Ash River Lab and the University of Minnesota module facility, the NOvA scientists, and all of the professionals and students building this detector,” said University of Minnesota physicist Marvin Marshak, Ash River Laboratory director. “This early result suggests that the NOvA collaboration will make important contributions to our knowledge of these particles in the not so distant future.”

Once completed, NOvA’s near and far detectors will weigh 300 and 14,000 tons, respectively. Crews will put into place the last module of the far detector early this spring and will finish outfitting both detectors with electronics in the summer.

“The first neutrinos mean we’re on our way,” said Harvard physicist Gary Feldman, who has been a co-leader of the experiment from the beginning. “We started meeting more than 10 years ago to discuss how to design this experiment, so we are eager to get under way.”

The NOvA collaboration is made up of 208 scientists from 38 institutions in the United States, Brazil, the Czech Republic, Greece, India, Russia and the United Kingdom. The experiment receives funding from the U.S. Department of Energy, the National Science Foundation and other funding agencies.

The NOvA experiment is scheduled to run for six years. Because neutrinos interact with matter so rarely, scientists expect to catch just about 5,000 neutrinos or antineutrinos during that time. Scientists can study the timing, direction and energy of the particles that interact in their detectors to determine whether they came from Fermilab or elsewhere.

Fermilab creates a beam of neutrinos by smashing protons into a graphite target, which releases a variety of particles. Scientists use magnets to steer the charged particles that emerge from the energy of the collision into a beam. Some of those particles decay into neutrinos, and the scientists filter the non-neutrinos from the beam.

Fermilab started sending a beam of neutrinos through the detectors in September, after 16 months of work by about 300 people to upgrade the lab’s accelerator complex.

“It is great to see the first neutrinos from the upgraded complex,” said Fermilab physicist Paul Derwent, who led the accelerator upgrade project. “It is the culmination of a lot of hard work to get the program up and running again.”

Different types of neutrinos have different masses, but scientists do not know how these masses compare to one another. A goal of the NOvA experiment is to determine the order of the neutrino masses, known as the mass hierarchy, which will help scientists narrow their list of possible theories about how neutrinos work.

“Seeing neutrinos in the first modules of the detector in Minnesota is a major milestone,” said Fermilab physicist Rick Tesarek, deputy project leader for NOvA. “Now we can start doing physics.”

Note: NOvA stands for NuMI Off-Axis Electron Neutrino Appearance. NuMI is itself an acronym, standing for Neutrinos from the Main Injector, Fermilab’s flagship accelerator.