Stephen Hawking Amazes at Fermilab

Few questions are broader or more all-encompassing than "Where did the universe come from?" On May 10, 1989, Stephen Hawking, Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Cambridge University, arrived at Fermilab to join other scientists in seeking answers to this question. Hawking participated in the Wormhole Workshop organized by the Fermilab Astrophysics Group and gave a public lecture entitled "Black Holes and Their Children, Baby Universes." Hawking also authored a best-selling book, A Brief History of Time - From the Big Bang to Black Holes.

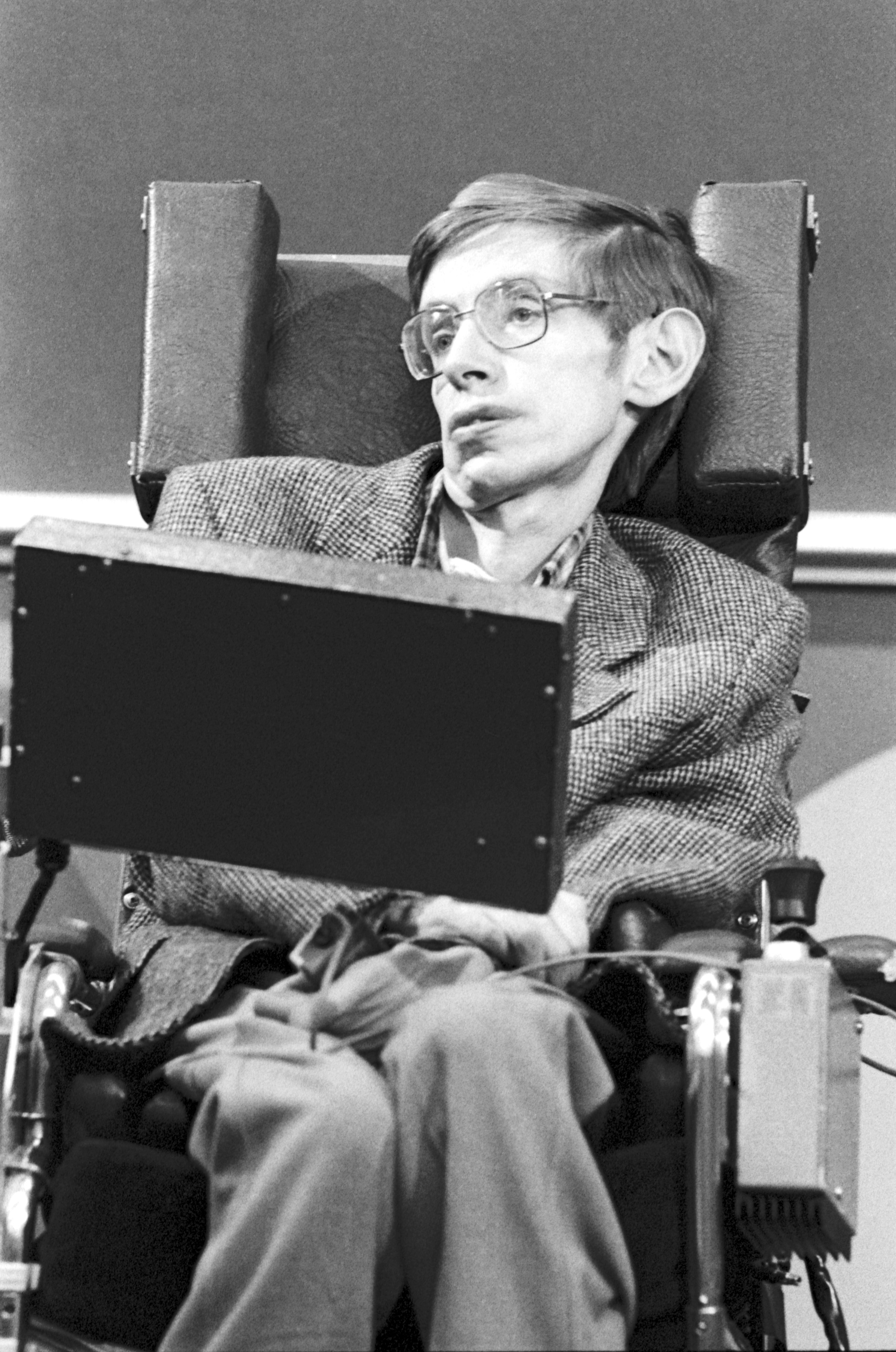

Hawking's third visit to Fermilab began with a press conference on May 10 in 1 West. The press conference was well attended by the media, including WBBM-TV, WMAQ-TV, the Sun Times, the Associated Press, and local news outlets.

Rocky Kolb, who co-heads the Fermilab Astrophysics Group, introduced Professor Hawking: "There have been two great developments in 20th-century physics - Einstein's Theory of Gravity, and Quantum Mechanics. By the end of the 1920s, the broad outline of the modern form of these theories had been developed. For the last 60 years the two theories have existed as separate edifices, and perhaps the most fundamental challenge of modern physics is to develop a single theory of quantum gravity to encompass these two revolutionary ideas... No one has been more successful in exploiting physical effects of quantum gravity than Stephen Hawking."

Hawking covered topics ranging from his concept of God to the possibility of time travel. When asked about his belief in God, Hawking replied, "I don't believe in a personal God. I wouldn't claim that my view of God is new. It is rather similar to that held by Einstein."

Hawking also believes that time travel as described in science fiction will not be possible. Such time travel might allow us to alter our own pasts, and Hawking said, "If it were [possible], we would have seen people from the future." Hawking explained that while particles could travel back in time, they do not alter the past.

When asked if he would achieve a single theory of quantum gravity, Hawking responded, "If we find a complete unified theory, it will be as a result of the work of many people. I hope to play a part, but any individual contribution will be small. It is possible that it could come within my lifetime."

Hawking also addressed several of the major questions facing cosmology. Asked about the possibility of looking beyond, or before, the creation of the universe, Hawking said, "You can't go back beyond the Big Bang. Time is defined only within the universe. To ask what happened before the Big Bang is like asking what happens north of the North Pole."

The two most important cosmological problems, Hawking said, are to discover why the cosmological constant is zero and why space-time has three dimensions of space and one of time. "Wormholes can probably answer the first question and possibly the second," he concluded.

Does Hawking ever find his work so far-fetched that his life no longer seems real? "I have enough practical problems to keep me in touch with reality," he quipped.

The press conference was marked by periods of quiet anticipation as Hawking formed his replies to questions on a special computer attached to his wheelchair. Diagnosed more than 20 years ago as suffering from ALS, or Lou Gehrig's disease, Hawking now communicates through a computer program called Living Center and a speech synthesizer. He often apologizes for the American accent of the synthesizer.

Though physically limited, Hawking has said his disability has given him more freedom to think. In 1974, Hawking showed that Black Holes, so-called because nothing, not even light, can escape their immense gravity, should actually emit radiation. In 1988, Hawking and Roger Penrose received the prestigious Wolf Prize in physics for their work on singularities - dimensionless points in space-time with infinite densities and irresistible gravitational pull.

The Wormhole Workshop addressed another important concept in cosmology. Wormholes signal the creation of baby universes. They may also answer fundamental questions about the nature of time and space. The workshop began May 10 with a colloquium presented by Hawking and ended on May 13. Approximately 50 scientists from around the world attended the workshop.

On May 13, Professor Hawking gave a public lecture through the Fermilab Lecture Series. His talk provided a non-technical view of the development and significance of Black Hole theory. Tickets for the lecture were sold out well in advance of the Saturday evening event.

Hawking discussed some of the implications that the existence of Black Holes might have on our lives. In particular, he addressed the possibility of using Black Holes to travel through space and time. Hawking said, "If there are objects called Black Holes, which things can fall into, but not get out, there ought to be other objects, that things can come out of but not fall into. One could call these White Holes. One might speculate that one could jump into a Black Hole in one place, and come out of a White Hole in another. This would be the ideal method of long-distance space travel... all you would need would be to find a nearby Black Hole."

Unfortunately, this method of space travel would be extremely unstable. Hawking explained, "...the slightest disturbance, such as the presence of the spaceship, would destroy the wormhole, or passage, leading from the Black Hole to the White Hole. The spaceship would be torn apart by infinitely strong forces. Anyone care to buy a ticket for the Titanic?"

Hawking also explained how baby universes form from Black Holes which have evaporated, or lost their mass through emitting particles and radiation. "What will happen then to objects, including possible spaceships, that fell into the Black Hole? A small, self-contained universe branches off from our region of the universe. This baby universe may join on again to our region of spacetime," said Hawking.

Hawking has been particularly interested in Black Holes and related objects because they may duplicate conditions at the instant the universe was created, answering the question "Where did the universe come from?"