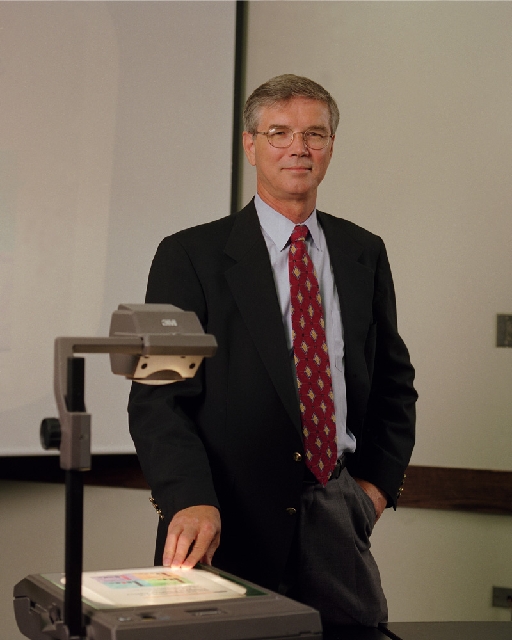

Ken Stanfield's standard as the Deputy Director: What's best for Fermilab?

Ken Stanfield's 17 years as Fermilab's deputy director have created a unique legacy. "Ken Stanfield has approached every issue with a single standard: What is best for Fermilab?," says former Director Michael Witherell. "He was asked to take on some of the most difficult problems at the laboratory, and he always agreed. The positive results of his involvement are everywhere on the Fermilab site. To take just one recent example, his behind-the-scenes contributions to NuMI were critical to the completion of that project."

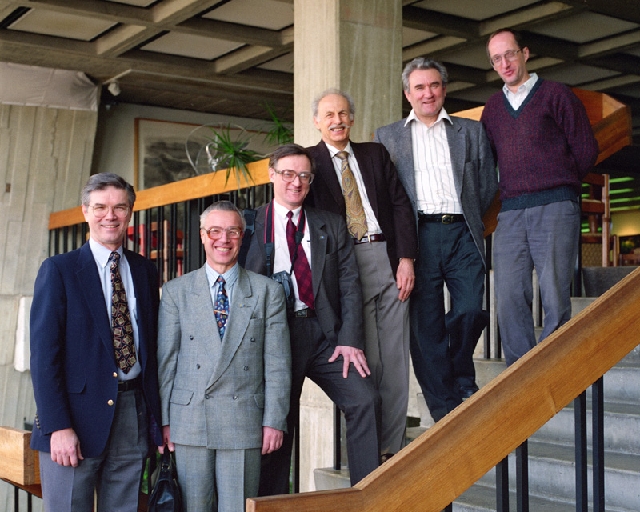

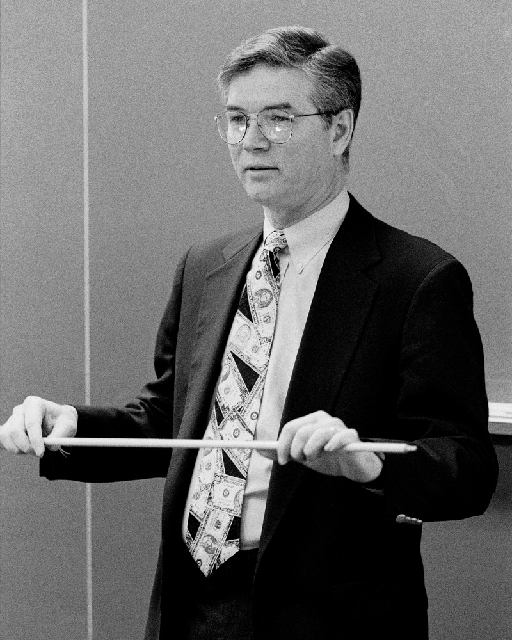

Stanfield (Ph.D., Harvard University, 1969) has played many roles since joining the lab permanently in March 1977 as a Proton Department physicist. His promotion to associate head of the department took just three months (June 1977). Over the years, he has served as head of the Proton Department; head of the Experimental Areas Department; Business Administration Section head; head of the Research Division (now the Particle Physics Division); and, since 1989, Deputy Director.

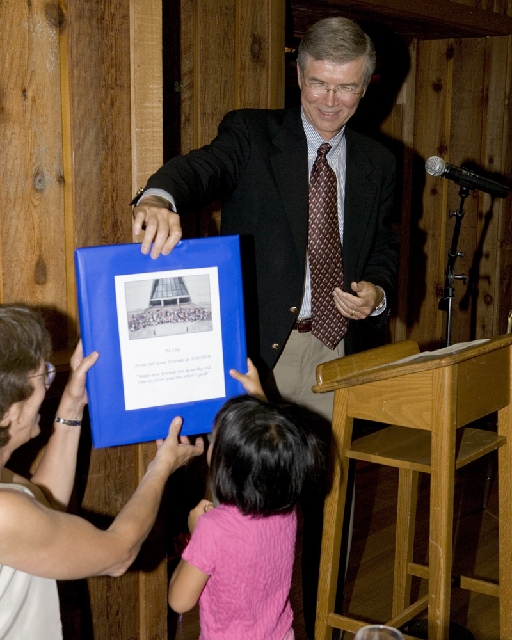

Stanfield steps down as deputy director today, with Young-Kee Kim taking over the post officially on July 1. Stanfield will become special assistant to the director, continuing his work on preparing the bid by Universities Research Association, Inc., with the University of Chicago as its new partner, in the contract competition to manage Fermilab for the Department of Energy's Office of Science.

"I have appreciated enormously that Ken was willing to lead the effort for URA in the contract competition," says Fermilab Director Pier Oddone. "With his usual competence he has quickly become an expert in the arcane art of these competitions. He could have a whole new career in front of him!"

While Stanfield might decline that particular honor, he accepted the assignment with his usual professional approach. "When Pier became director (in July 2005)," Stanfield says, "he had the right to choose his own team. So the first thing I did was offer my resignation. I also offered to help in any way Pier thought was useful."

Oddone found Stanfield's help invaluable. "Ken has been of immense help to me," Oddone says. "His deep understanding of laboratory operations and the scientific program have made him uniquely effective. No one else has a better pulse of the laboratory than Ken."

Then came the time when Oddone said: "By the way, I'd like to have you be the manager on the contractor proposal."

"It was Pier's idea," Stanfield says. "I was in a good position to know the lab, and the people in it. . .and to bring the resources necessary to the proposal process. That will be going on at least through October 1. Then I will assist Pier in the transition period until the new contract takes effect."

And then?

"And then," Stanfield says, "I'm going to examine what's next. I haven't made any decisions, and it's pretty open. But I'm going to take my time."

Stanfield has been a manager for so much of his career that his physics work can be overshadowed. He was one of the lab's original users in 1968 ("I went to the first Users' Meeting in the Village Barn"), and a member of Experiment 7 (Elastic Scattering), which ran from 1970 to 1975. He worked on Charm Search experiments E357 and E472; with E516 (Photoproduction of Charm Particles) he was one of the founding members of the Tagged Photon Spectrometer collaboration. "That was a very successful scientific endeavor," Stanfield says. "I had a lot to do with building the spectrometer, especially the tracking chambers. Of course, that's ancient history now."

The appointments in the Proton Department, Experimental Areas and Research Division appear to follow logically; the Business Administration appointment would seem unusual, except to those familiar with the ways of founding lab director Robert Wilson.

"This was a fantastic thing about Bob Wilson," says former Fermilab Director Leon Lederman. "Senior scientists moved around the lab and gained management experience with different areas. We had a whole cadre of senior scientists who were exposed to management responsibilities. If they had good management skills, we found out. If they had no skills, we found out in a hurry."

Lederman recalls Stanfield as an immediately effective manager. "Ken was particularly good," he says. "He was unflappable, calm, but decisive in what he wanted done. He always had a keen understanding of the priority of the lab, and that was the physics. Ken took well to management, even though it cut into his research. That kind of service has been the heart of this lab, and it's been demonstrated by people like Ken."

Stanfield recalls the Business Administration duties wryly, noting he held the position only while Bruce Chrisman was away from the lab working (temporarily, it turned out) at Yale University. "Leon appointed me," Stanfield says, "and I would describe that time as a great learning experience for Ken Stanfield. I learned a lot from those people over there. Jim Finks was my deputy, and he had a lot to do with running things while I was there. It was actually very good experience given my duties in the last numbers of years."

John Peoples says that when he realized he would succeed Leon Lederman as lab director in 1989, he knew he wanted Stanfield as his deputy director, after working with him in the Proton Department. Stanfield accepted, and soon took on a role greater than either he or Peoples had anticipated. "Soon after I became director," Peoples recalls, "I delegated the big collider detectors to Ken, along with a lot of other things, including the budget. I was consumed with trying to get the Main Injector approved in DOE and Congress. When the Tigers [DOE inspection team] began to circle Fermilab in early 1992, I asked Ken to organize our response. He did a terrific job. In late 1993, the SSC collapsed and I agreed to serve as the Funeral Director. For nine months, Ken ran the day-to-day operations of Fermilab. He had the honor of closing Eola Road to the public. I concluded it is easier to get people to change their sex partners, than to change their driving habits."

Peoples also claims a sort of left-handed credit for Stanfield's original move to Fermilab. "In early 1972," Peoples says, "I was invited to Purdue to give a talk on the photoproduction experiments that I was planning to work on at Fermilab. At the time Ken was an assistant professor, and his senior professorial colleagues at Purdue wanted him to work on an experiment at Brookhaven. I didn't know about the last wrinkle, so without any inhibitions I told them in colorful language that the BNL experiment was a terrible experiment and (Stanfield) should be encouraged to work on an Argonne experiment, which he had proposed and for which he was the spokesperson. He did the Argonne experiment, and I suspect it sped the day when Ken came to Fermilab."

Peoples also appreciated the role-reversal when, as former lab director, he became director of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. "When I stepped down as director to look at the sky, Ken became my boss," Peoples says. "For some reason he tells people that it was easier to work for me than supervise me. I enjoyed his support and the opportunity just to talk to him for the past thirty years. I will miss him."

However, as Stanfield emphasizes, he isn't going anywhere, except back and forth daily to the special office in Batavia to continue working on the contract competition.

In nearly 30 years, Stanfield has watched the lab change from fixed-target experiments to collider and neutrino programs, to Run II of the Tevatron and to questions about what comes afterward. Viewing his time as deputy director, Stanfield says "life has gotten a whole lot harder on us, with the budgets and with declining resources." He has remained focused on what he sees as the constant, in every circumstance.

"What has energized me is that this is a great national laboratory, with great science," he says. "I've been in a position to have a certain influence, to have a reasonable impact on the landscape, and just to help make things happen. I've been in a position to see and understand the great science that comes out of the lab. That's what has always motivated me."