Breaking New Ground in Human Relations, by Edwin L. Goldwasser

Scientists are restless in these days of social strife. As a group, they tend to be concerned humanitarians. They believe in the intrinsically human value of basic research, yet they are repeatedly confronted by its military applications. At the same time, they find their science to be relatively dissociated from major social problems. As a result some are seeking ways to involve themselves more directly with the problems of our society and our cities. Such re-dedication of purpose must certainly be respected, but the constructive pursuit of science should not be abandoned. It has played a dominant role in the emergence of man from darker times than these, and it can still contribute crucially to further cultural, social and technological progress.

At the National Accelerator Laboratory (NAL), we have found it possible to pursue scientific objectives and, at the same time, to be more than mere spectators of the crises which grip our society. We have been able to channel our recruitment, purchasing and contracting policies in ways that contribute to the solution of some of these problems. This is possible, in part, because we are a large and influential scientific enterprise.

Our experience, however, indicates that all scientists, in the pursuit of their research, may have a real opportunity not only to contribute, through their science, to the intellectual and cultural achievements of mankind, but also lead the way in demonstrating that any business enterprise can make a significant contribution to improving the plight of the under-privileged, the undereducated and the underemployed.

The Issue Is Joined

The directorate of the National Accelerator Laboratory would in any case have been dedicated to an active program in support of the principles of minority rights in and around our laboratory. However, early in our history, in the summer of 1967, we had the issue thrust sharply upon us through the refusal of the Illinois State Legislature to pass an open-housing statute.

In response to that action Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. sponsored a tent-in at the newly chosen accelerator site near Batavia, outside of Chicago. This was his protest against the location of a national laboratory in a state whose legislature had almost defiantly refused to enact any open-housing legislation. In the course of that controversy, we had to face a critical decision. We were urged to clarify our position on minority rights by refusing to work on the project at the Illinois site. After much careful thought we decided to ignore this advice and elected to press ahead with the project.

Chicago, like other major American cities, was in a state of crisis. There was an urgent need for jobs, education and housing, particularly for the Negro population. We believed that with a project as large and potentially influential as ours we could make important contributions, not by turning our backs upon the area and its problems, but by consciously conducting our affairs in a manner which would help to solve some of those problems.

Policy Statement Issued

One of our first actions was to promulgate to members of our staff and to many of our outside contacts the "Policy Statement on Human Rights," reproduced here. Each new employee receives this document, and it is displayed prominently throughout the laboratory. As part of that policy, at the time of the open-housing fight, we supported Dr. King in his protest. In addition, we petitioned members of the State Legislature with an urgent - though futile - plea for passage of a strong open-housing statute.

Staff Action

"We must play an active role in implementing the policies that we espouse."

E.L.G

Of course, our activities in these matters have gone beyond the simple enunciation of strong words. These are not what really count. Rather it is the substantive action of the laboratory staff. This action is bound to be closely tied to the working-level understanding of the depth and seriousness of the commitment of the administration to its stated policies. We, therefore, believe that we must play an active role in implementing the policies that we espouse. Rather than delegating total responsibility to people with expertise in these areas, the directorate of the laboratory has acted to implement its philosophy. As this is given public exposure, it exerts influence not only outside the organization, but inside as well. We believe that it has a strong impact on our recruiting, purchasing, contracting and all other facets of the life of our laboratory.

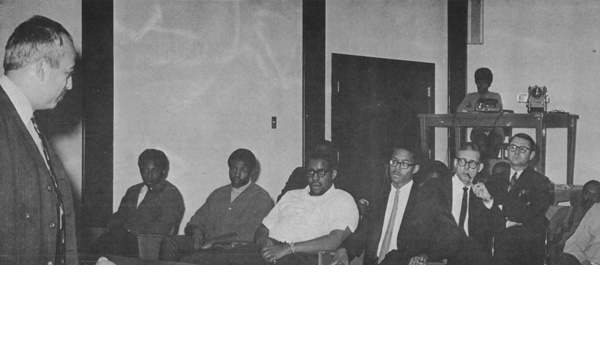

During the last two years, we have made personal contacts with leaders of minority organizations as well as with many Chicago area and national experts on minority problems. We have appeared as witnesses at several town council meetings, supporting the adoption of urgent open-housing legislation.

Certainly the most important single step we have taken is the establishment within our laboratory of an Equal Opportunity Office, headed by Kennard Williams. It has received enthusiastic assistance from the joint venture known as DUSAF, our architect-engineering firm.

Training Unemployed

One of the first programs in which we participated was the training of 100 young, hard-core unemployed. Two 10-week, preapprenticeship training sessions in the operation of heavy earthmoving machinery were sponsored by Local 150 of the International Union of Operating Engineers. Of the initial 100 trainees, 86 completed the course. Of these, six achieved full journeyman standing while the remaining 80 qualified as apprentices. Of the total, 72 are still known to be working as operating engineers. Many have worked or will work on NAL construction jobs.

In another pilot program, a group of young men between the ages of 18 and 30 were recruited from the inner city and trained for skilled technical jobs. After an initial orientation course at NAL, the men were sent to Oak Ridge, Tenn., where they were enrolled in the Training and Technology Program conducted by Oak Ridge Associated Universities. Representatives of NAL's Personnel Office, acting as guidance counselors, kept in close touch with the trainees, who compiled an outstanding record in the training program. On completion of the 30 week course, the men returned to NAL to take up positions as machinists, draftsmen and mechanical and electronic technicians.

In the screening process, overriding emphasis was placed on the apparent motivation of the interviewees. No criteria were imposed concerning previous school or job achievement, police or prison records.

Black Industries

NAL has also developed a list of "Black industries," consisting of minority-group contractors and suppliers who operate businesses relevant to the Laboratory's present and future needs. This effort has been most successful where contracts below $10,000 are involved. Approximately 40 per cent of such contracts for work in t h e old village of Weston, awarded during the past six months, have gone to Black contractors.

Where larger contracts are involved, there are relatively few minority-group contractors willing to undertake the jobs. For these contracts NAL presents to the bidders, at a pre-bid conference, a sample plan of an affirmative action program for establishing training and jobs for members of minority groups. Bidders are then required to submit, with their bids, their proposed affirmative action programs. Each proposed program is considered together with other features of the bid. Unless it represents a strong positive selection of program elements from the Laboratory's sample plan, the bid may be rejected. Furthermore, when a contract is awarded, the proposed program becomes a part of the contract, and failure to implement that program may be interpreted as breach of contract. So far we have found that contractors, although in some cases reluctant to institute such programs on their own initiative, welcome the opportunity to do so under the external pressure represented by our contracting procedures.

Black Specialists Sought

We have not had uniform success in staffing our laboratory with minority-group employees. Among our non-professional employees more than 20 per cent are Black. Two of the four persons who interview prospective employees are Black. Nevertheless, the more specialized the job bracket, the smaller is the representation of Black applicants. We believe that this is not a shortcoming of our recruiting procedures but rather a reflection of inequities that have been operating for decades.

Career Guidance

In an effort to remedy this situation - to stimulate a flow of inner-city school students into curricula and training programs that will later qualify them for highly skilled technical jobs and professional scientific positions - the Laboratory has initiated a joint program with the Council for the Bio-Medical Sciences. That group has been remarkably successful in guiding qualified Black students into careers in the bio-medical sciences. We hope for similar success in the preparation of young people for careers at NAL in engineering and the physical sciences.

A Unique Opportunity

The National Accelerator Laboratory clearly provides a unique opportunity to contribute to one of the most important activities of man - the discovery of the true nature of the world in which he lives. In the pursuit of that activity, however, we must not ignore, and have not ignored, other urgent problems which are pressing upon our society today. The traditional stance for an organization such as ours, attempting to do a difficult job on a tight schedule, is to "play it safe." On a matter like open housing, for example, it is tempting not to antagonize the anti-open-housing interests. In large construction projects, it is tempting not to impose a stiff non-discrimination policy and thus risk the loss of potential contractors. In purchasing it is easier to use only the well-established and better known vendor. In employment it is tempting to hire the trained rather than to train the ready and eager underemployed.

Adaptation Needed

"The condition of our society demands a long-range view and, in fact, we have found that this is also the best short-range approach."

E.L.G.

But the condition of our society demands a longer-range view, and, in fact, we have found that this is also the best short-range approach. We have been willing to accept whatever incremental cost might have been associated with the implementation of these programs, but we believe, in fact, that such a cost has not materialized. In any case, we are convinced that the cost to society of solving these problems through adaptation of its normal activities to these goals is ultimately much less than the cost of initiating special activities, ad hoc, to provide crash solutions which are likely to be of only temporary value.

Local Housing Ordinances

Although the Illinois General Assembly has continued to resist passage of a strong open-housing statute, local ordinances have been adopted in more than 30 communities surrounding the laboratory. Construction is proceeding at the laboratory site. Black workers are involved. Recruitment for technical jobs is proceeding. Black citizens are being hired and trained. Procurement of technical components is underway. Black industry is contributing. It is more appropriate to say "because of" than "in spite of" these actions, our design and construction are on schedule and we have had no significant delays.

Seek Opportunities

It is in part the size of our project which has made it possible for us to achieve some success in these early programs. It is because we are large that we can justify the employment of a staff with a full-time responsibility to discover opportunities through which the laboratory can contribute to the solution of social problems.

But our position as a large enterprise is not unique in the scientific community. In fact, basic science in the United States has become a large enterprise. Its managers control the hiring of many people. They have great influence in educational institutions. They supervise the spending of research funds in excess of a billion dollars annually. They have some influence over the expenditure of development funds at 10 times that annual level.

Yet most individual scientists are members of relatively small research groups or university departments, which can not justify an "opportunity" staff. How can a scientist in a small research group make a contribution?

Influence For Social Ends

Perhaps the most effective way is to use his prestige and influence in the university or industrial organization of which he is a part to establish and to enforce strong policies with respect to minority rights, education, training and employment opportunities. But scientists may wish, in addition, a more direct involvement - one which bears the stamp of their profession. This might best be done through united action as a national community or scientists. As such they could support a major investment of funds and effort. These could be used to establish a national office and perhaps regional clearing-houses where expert advice could be available on matters of recruiting, training and employment of minority-group members, on methods of purchasing and contracting in a manner that will stimulate minority-group involvement in our industry and economy. Any scientist who wished to channel his activities in such a way as to make a positive contribution in this area could avail himself of these services. In this way, fundamental science, which has certainly been one of the most rewarding enterprises of mankind, could not only continue to contribute to the intellectual and technical growth of our society but could simultaneously implement imaginative programs reflecting the dedication of scientists to the precepts of human rights and dignity.

The Author

Dr. Edwin L. Goldwasser is deputy director of The National Accelerator Laboratory. He is a physicist, who received his bachelor's degree at Harvard University in 1940 and his Ph.D. in physics at the University of California-Berkeley in 1950. He came to NAL from the faculty of the University of Illinois-Urbana, which he joined originally in 1951. He served on the National Academy of Sciences committee to evaluate possible sites for location of NAL.