Fall Prairie Activities Announced

Fermilab will participate in observance of "Illinois Prairie Day" on Saturday, September 25. This day has been set aside by Illinois Governor Walker to honor the remaining prairies and prairie restoration projects in the state, and a number of these sites will be open to the public on Prairie Day. Special tours and programs will be offered under the sponsorship of the Illinois Department of Conservation.

At Fermilab Robert F. Betz, a prairie expert who heads the Advisory Committee for Fermilab's prairie restoration project, and Anthony R. Donaldson, chairman of the Fermilab Prairie Restoration Committee, will present a special program, "Prairie Panorama," at 8 p.m. in the Auditorium. Admission is free and the public is invited.

An exhibit of prairie photographs by Donaldson, prints by Bobbie Lively, Roberta Simonds, and Henrietta Tweedie, and ceramics by Ruth Duckworth will be on display in the Central Laboratory Building, second floor lounge area, through October 25.

Betz brings to Fermilab a vast reservoir of knowledge about the prairie. A professor of biology at Northeastern Illinois University, he is the author of several well-known prairie-related references. He travels throughout the state identifying and organizing the preservation of the few remaining prairie remnants in Illinois. His enthusiasm and respect for the real prairie as an important ecological system are reflected in his dynamic lectures.

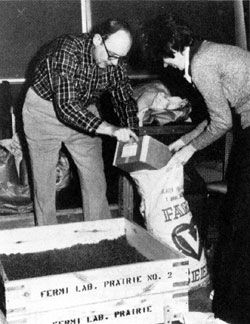

Donaldson, an engineer in the Accelerator Division, and his wife, Rene, of Technical Information, have been the leaders of the prairie restoration committee's work at Fermilab for nearly three years. Under Betz's guidance they have organized the seed harvesting, the planting preparations, and the weeding and maintenance vital to the success of the project.

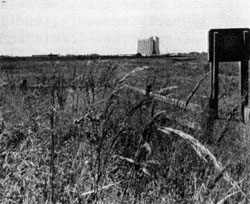

Fermilab's prairie restoration project is on its way to becoming the largest prairie restoration in the United States. Sixteen of the 660 acres in the center of the Laboratory's Main Accelerator have now been planted with seeds from two of the area's outstanding prairies - the 10-acre restoration at the Morton Arboretum in Lisle and at the Gensberg-Markham Prairie in Markham, Illinois, as well as at scattered prairie remnants.

Since the prairie planting in the Main Ring is for the time being inaccessible for viewing, a small sample patch - a demonstration plot - has been planted alongside Road D, opposite the buffalo pasture. The demonstration plot, surrounded by a rail fence clearly visible from the road, is a mini version of the prairie that will eventually emerge inside the Main Ring. The small plot can be kept weed-free and the plants there thrive more generously than the large tracts in the Main Ring where the emerging prairie species must battle the Eurasian weeds that have taken over since the land was put under cultivation in the 1800's.

Once the prairie inside the Main Ring is established, the only measure necessary to insure survival of the long-lived prairie grasses is a supervised "burn" every other spring. Prairie plants, which are perennials with long, well-developed root systems, can withstand recurrent fires which the Eurasian weeds cannot. It requires at least two years after planting a restoration before there is enough vegetation to sustain a good fire.

Volunteers will be needed again this Fall to harvest seeds for next year's planting. Under the Donaldsons' leadership, these people will go out on October 2, 9 and 16, 1976 with pails and grocery bags, trying to bring back several hundred pounds of the precious seeds. "We can plant as much seed as we can collect," Donaldson says. "and we would like next year to double the acreage already planted." Eventually, the prairie planting at Fermilab will furnish its own seeds to complete the project, and a modified agricultural combine can be used for the harvesting.

Several hundred volunteers have been associated with the seed harvest in the past two autumns. Their vision of returning the land to the unique and beautiful ecosystem which the true prairie represents clearly motivates all of the hard work it involves.

To many people the word "prairie" brings to mind visions of flat or slightly-rolling farm land dotted with houses and trees, and covered by neat rows of corn, wheat, and soybeans. Many are unaware that "prairie" actually refers to a vegetation type which covered much of the United States for thousands of years, and which has nearly disappeared since the time of European settlement. The true prairie was called a "sea of grass" in early accounts, and it extended from western Indiana to the Rocky Mountains with little interruption. Lewis and Clark described it as "good land, covered with grass...void of timber."

While dominance by grasses is one of the most distinctive features of prairie, it also contains many wildflowers and broad-leaved plants which add to its beauty and diversity. The "summer prairie" has a different look than the "autumn prairie." Both evoke the praise and admiration of those who study the unusual ecosystem. In Illinois there are three main types of prairie: tall grass prairie, which is characterized by grasses such as big bluestem and Indian grass that reach heights of seven feet or more; sand prairie, which contains grasses and broad-leaved species that are adapted to dry conditions, and hill prairies, containing mid-height grasses such as little bluestem and side oats gramma which reach heights to 2 to 3 feet. The tall grass was once one of the most remarkable features of Illinois. It extended across most of the central part of the state and created the rich, dark soils that make some of the best cropland in the world. The sand prairies are restricted primarily to the large sand deposits along the Illinois and Mississippi Rivers, and hill prairies occupy the south and west facing bluffs along most major streams in the state