Prairie Project Moves Forward to Recapture Past

The first 13 acres of a prairie restoration, on 668 acres in the center of the Fermilab main accelerator, were planted in early June. Dr. Robert F. Betz, chairman of the Advisory Committee and a world-famous prairie authority and professor of biology at Northeastern Illinois University, directed the planting with Ray Schulenberg, curator of the herbarium at the Morton Arboretum, and members of the Fermilab Prairie Committee, headed by Tony Donaldson.

Fermilab's Grounds Crew joined the small army of people who have already contributed to the project, expected to produce the world's largest restored prairie and to become an important center of botanical research. Applying their experience with the rich soil found on the Fermilab site, Fermilab's Grounds Crew carried out two plowings of the prairie ground last fall and several discings this spring. With the assistance of Dave Sauer, head of Site Services, and Rudy Dorner, Site Manager, the historic planting schedule was finalized several weeks ago.

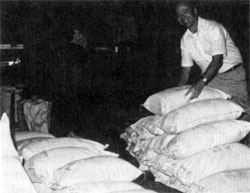

More than 400 pounds of seeds including four grasses and fourteen flowers were sown. Representing species typical of this region of Illinois, the seeds were gathered by hand during three weekends last October. More than 200 people from the Chicago suburbs and from Fermilab traveled to the prairie remnant at Markham, Illinois, and to the restoration at the Morton Arboretum to harvest ripe seeds of the plants known to have grown on the Illinois prairie of pre-settlement days.

A "thrashing bee" followed to remove chaff and foreign matter from the seeds, which were then bagged and stored in a closet in the Central Laboratory. In April the precious seeds were "stratified" - mixed with vermiculite and placed in the cooler of the old cafeteria in the Fermilab Village to simulate the normal effects of winter.

"We are speeding up a process that takes natural forces hundreds of years to complete," Dr. Betz notes. If the first segment of the project is successful, with satisfactory germination and enough growth so that new plants become established this year, another 10-15 acres can be planted in 1976. These two plots, when mature, could furnish seeds for much larger tracts, perhaps 100-200 acres each, and in ten years the project will be complete.

To the uninitiated, "prairie" is the name attributed to grassy, treeless fields, generally associated with the flat open spaces of Midwestern United States from Ohio to Kansas. "Prairie," (from the French, meaning "meadow") is actually the descriptive name given by the Europeans who first came to the end of Lake Michigan and found the seemingly endless grasslands of Illinois.

To the biologist, however, the prairie is a complicated ecosystem. It consists of grasses, with roots sometimes twenty feet long, growing six feet tall, sprinkled with a wide variety of flowering species which bring a constantly shifting pattern of beautiful color to the expanse where it grows, as each variety comes into bloom. Birds, insects, and wildlife accompany this pattern.

The inter-relationship of the plant life, the animal and insect life, and the survival of the ecosystem through fires and natural hazards, has become the basis of a field of biology similar to the study of forests. Its preservation is viewed by biologists much as is the survival of endangered animal species. Professionals like Betz and Schulenberg miss no opportunity to preserve small prairie remnants, such as in pioneer cemeteries and along long-established railroad tracks. Working with representatives of The Nature Conservancy, they bring to Fermilab's restoration the sum of all that is known about a vanished biological era on the North American continent.

The first pioneer settlers ignored the prairie, thinking it poor soil because it bore no trees. They settled instead near water and in groves of trees. But the rich soil produced by the prairie ecology, once it was discovered, was soon brought under agricultural subjection. The steel plow was invented to subdue the dense root structure of prairie growth. By the time of the Civil War, the prairie had nearly vanished. What grows now are weeds, imported from Europe with settlers' seeds, seen by biologists as aggressive, dominating, undesirable plants, often referred to as "old world weeds."

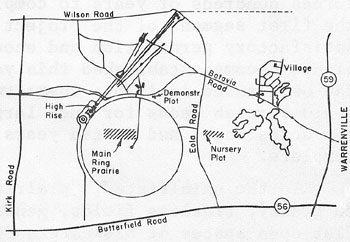

The rectangular area recently planted in the center of the Fermilab main accelerator is clearly visible from the upper floors of the Central Laboratory. The volunteers also maintain a small plot just off Road D (see map below) in which a sampling of the same species in the Main Ring tract were planted last summer for viewing and study by the public. In another plot, south of Eola Road, a "nursery" plot, adjacent to the Laboratory nursery, contains other rare species, planted in rows for cultivation, from which seeds can be harvested for sowing in the Main Ring over the next few years.

Anyone interested in participating in or learning more about the Fermilab restoration is urged to contact members of the Fermilab Prairie committee.

Work assignments are mailed out regularly to volunteers for planting, weeding, and other special projects. They report as they are able, but more hands are always needed. Volunteers range from students and other men and women of all ages. Everyone is welcome.